Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

Chichén Itzá was built in two major construction waves. Old Chichén was the earliest phase, built in the southern part of the site shortly after the founding of the city. Buildings here are in the regional classic Puuc Hills style similar to that found in neighboring sites like Uxmal, Labná, and Kabah.

Much of what we know about Old Chichén Itzá comes from hieroglyphic texts found inside these buidings. In contrast to the inscriptions found in the old kingdoms to the south, which centered around ruling lineages and the lives, investitures, military victories, and death dates of rulers, the inscriptions at Chichén Itzá deal with construction dates and ownership/sponsorship of buildings, as well as the memorialization of ceremonies performed within these rooms by historical high-status individuals.

"Some of the more conspicuous structural elements, like facades, doorways, lintels, and jambs are mentioned as being carved and finished at specific dates. Following the terms of these architectural features, one encounters the names of individuals who owned or sponsored entire buildings as well as single rooms in them. These names are constituent parts of rather elaborate phrases which feature titles, special occupations and offices, as well as genealogical and ethnical terms."

Voss, Alexander W., and H. Juergen Kremer (2000), K'ak'-u-pakal, Hun-pik-tok' and the Kokom: The Political Organization of Chichén Itzá. In The Sacred and the Profane. Architecture and Identity in the Southern Maya Lowlands, 3rd European Maya Conference, University of Hamburg, November 1998, Pierre R. Colas et al. (eds), 149– 181. Acta Mesoamericana 10, Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.

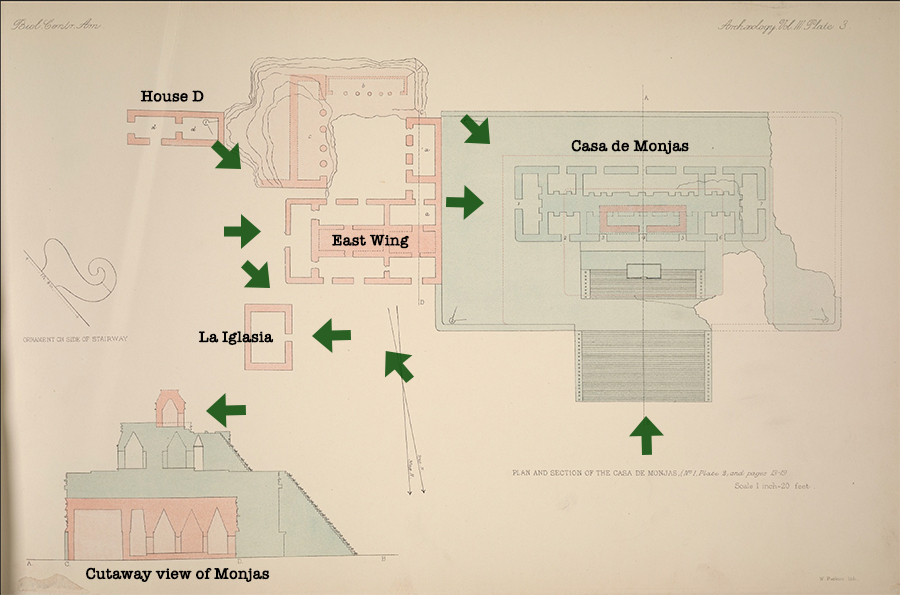

The early core of Old Chichén Itzá consisted of a network of structures interconnected by causeways emanating from the Casa de Monjas. These connected the Ossuary sub-temple (later covered by The High Priest's Grave), the Chacmool Temple (later buried underneath El Castillo), and the Casa Colorado to the north, and the Akab Dzip residential palace and other outlying groups to the south. This initial building phase took place during the sixty-five year period from 832 A.D. to 897 A.D.

Map adapted from Alfred Maudslay's Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Vol III, 1902.

Please click on GREEN ARROWS to jump to specific buildings, or keep scrolling to see all photos

Click here for an annotated Chichén Itzá reading list.

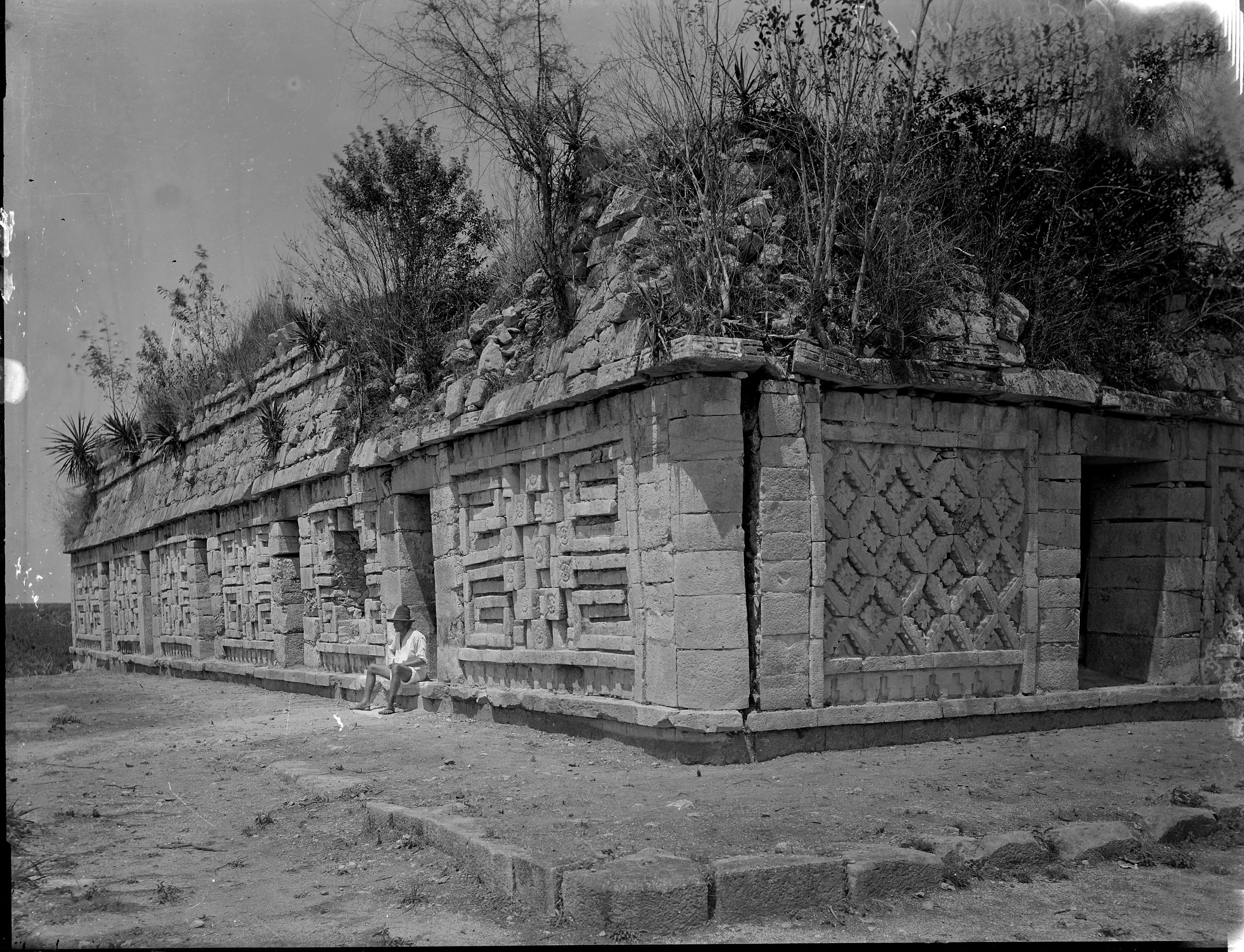

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

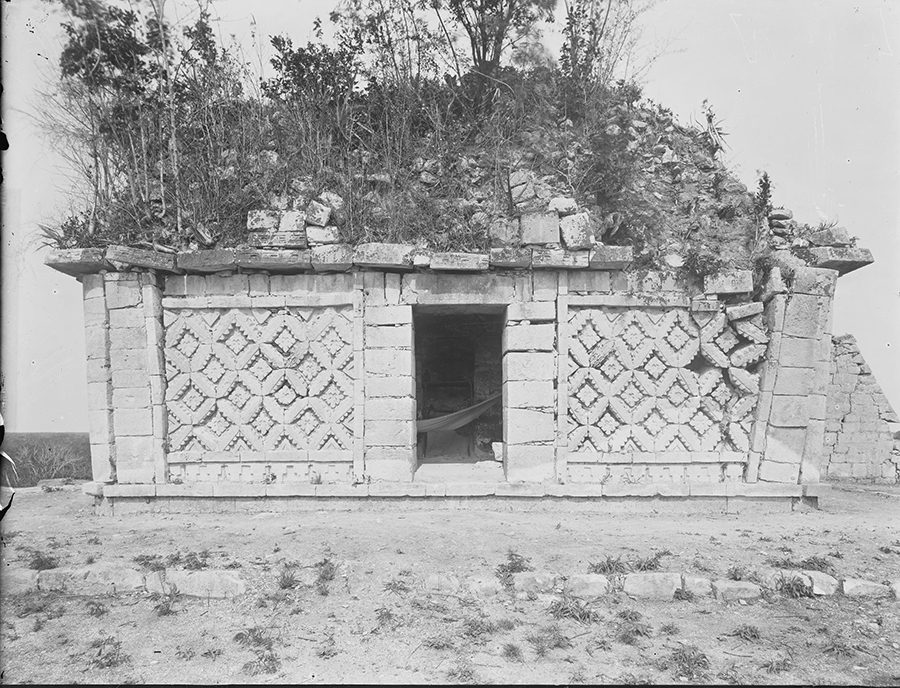

Maudslay remarked that La Monjas was the best preserved of all the major buildings at Chichén at the time of his visit in 1889.

"It consists of a solid mass of masonry, which I shall call the Basement, supporting a range of buildings on which another single-chambered building is superimposed...The basement is a solid mass of masonry, with slightly sloping sides and rounded corners, 165 feet in lengh, 89 feet broad, and 35 feet high.

"The basement, as we are told by Stephens, served as a quarry for the builders of the hacienda [Hacienda Chichén], the result being that a considerable portion of the south-west end has been removed entirely, and that a large breach has been made on the west side of the great stairway and tunnels driven in."

A.P. Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology. Volume V (Text). London, 1889-1902, p. 13–14.

In addition to its Puuc architecture, this building in interesting because of the inscriptions found written on lintels at the top of doorframes.

The personal, individual-oriented information which the inscriptions provide on the people who built, sponsored, dedicated, owned, and inhabited the first buildings of Chichén Itzá, have tempted scholars to reconstruct the social setting and the political system of the city from these data, but unfortunately the meanings of the glyphs are elusive and subject to various interpretations.

The Maya art historian and epigrapher Linda Schele believed the diagonal mat pattern seen here and common across the Maya Puuc Hills sites is diagnostic. Writing about this pattern as it appears in the façade of the North Building of the Nunnery Complex in nearby Uxmal, she has this to say:

"The flower lattice consists of crossed diagonal members with recessed centers and zigzag edges. Flowers lie in the diamond shapes formed by the diagonals. We think this lattice replicates a kind of flower-laden scaffolding once used in Maya ritual. But more important, sixteenth-centry Yukatek dictionaries gloss nikte'il nah (literally "flower house") as "an assembly house," and say that it is the same as a popol-nah, "a community house, where they assemble to deal with the affairs of state, and to teach dancing for community festivals."

When Maudslay worked at Chichen in 1889, he stayed in an apartment in the Monjas. I enjoy speculating that this might have been the apartment when Maudslay and his assistant Sweet stayed, because the photo shows signs of habitation & a hammock is stretched out behind the door opening.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

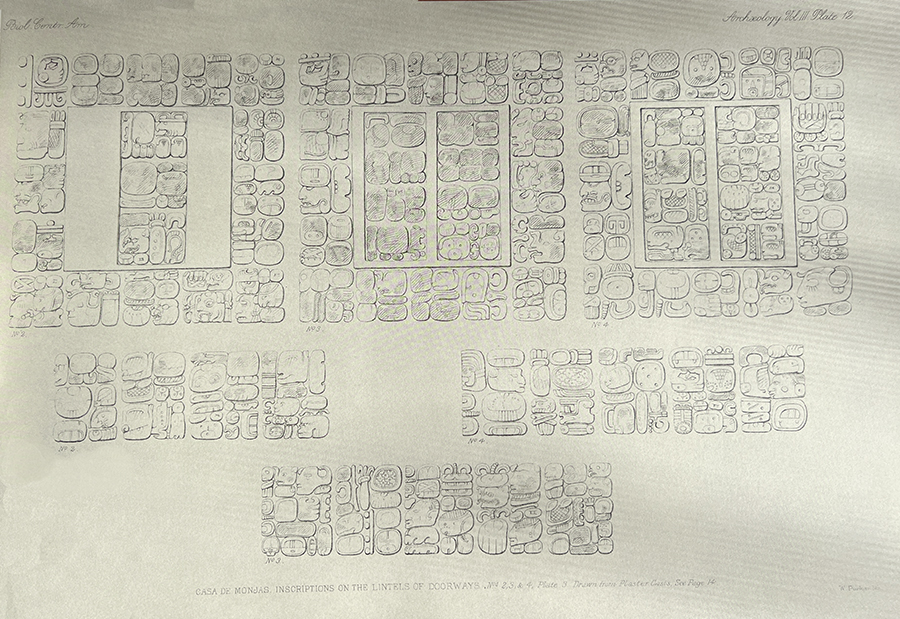

There are seven lintels inscribed with glyphs in the upper-story apartments of Monjas, one over each of its seven doorways. These lintels are all dated with a Maya Calender Round and Short Count Date equivalent to February 4, 880 A.D.

After each date, there is a short dedicatory statement referring to the carving of the stone for the home of some named individual. What is intriguing is that some scholars think the named owners of these rooms are a mixture of gods and high ranking Chichén Itzá officials of that time.

"The hieroglyphic texts at the Las Monjas building inform that certain houses belonged to gods, who were accompanied by other gods. Other houses belonged to actual human beings: Ixik K’ayam, the mother of K’ak’ Upakal, and Uchok, a male human being who probably also was a relative of K’ak’ Upakal. It is unclear to which houses the text refers, but perhaps the various rooms at the Las Monjas building were referred to, metaphorically speaking, as houses. If so, the Monjas thus housed both gods and human beings."

Eric Boot. Online resource: Amongst the Gods: Discourse and Performance in the Inscriptions at Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Mexico. Paper presented at the VI Mesa Redonda de Palenque, November 2008.

A.P.Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, London: R.H. Porter. Vol. III (Plates), Plate 12, 1889-1902

Maudslay described these apartment, commenting:

"The range of buildings contain seven chambers unconnected with each other, and each opening on to the terrace. The lintels of the doorways facing south are of plain stone, but those of the doorways at the east and west ends, and also of the two chambers facing north, are carved on the outside and on the under surface with hieroglyphic inscriptions.

"The three recesses on the north side, which correspond with the three central doorways on the south, also have carved lintels; and there can be no doubt that they were originally doorways which gave access to a room corresponding to the long chamber on the south side, and that this room was purposely blocked up in order to afford a secure foundation for a building to be erected above it. The inscriptions on the lintels are all much worn, and in some cases almost obliterated.

"The chambers were all paved with cement, which, in some parts, is still fairly preserved. The walls and roofs have been coated with plaster and painted with battle scenes and other designs; a very few small patches of these paintings still adhere to the walls, and it is just possible to make out figures of warriors 10 to 12 inches hight, with shields and lances in their hands. Blue, red, orange, and green were the colours used."

A.P. Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology. Volume V (Text). London, 1889-1902, p. 14 - 15.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

Maudslay observed that before the upper chamber could be built, the room underneath was filled in with rubble in order to provide a stable foundation. The break in the rubble at the bottom of the photo gives a glimpse of the upper molding of the old filled-up chamber below, while on the left is a portion of the balustrade exhibiting projecting rain-god snouts (minus the rest of the masks) which once decorated the stairway.

Exploring the quarry tunnels made in the west side of the stairway to provide stones for the building of the Hacienda Chichén, Maudslay discovered three older "basements" layered under the current basement, and even this third sub-basement appears to have been the remains of a cornice of a still earlier foundation -- "and thus we are led to the curious conclusion that when one of these buildings was found too small for the needs of the population or had failed to gratify their sense of propriety to the purpose for which it was designed, it was not left standing and additions made to it, but the buildings on the top were destroyed, and the basement used as a core for a larger foundation, on which new buildings were raised."

A.P. Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology. Volume V (Text). London, 1889-1902, p. 15–17.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

The East Annex of Casa de Monjas is the only part of the structure which lacks a "basement" and thus has rooms sitting at ground level. Maudslay continues:

"This method of enlarging the Casa de Monjas must at least have been partly abandoned, for the East Wing, which will now be described, is clearly an addition made after the basement had arrived at its present form. However, in this wing it is probable that the second process of enlargement was about to be carried out, for the two inner chambers had already been blocked up, doubtless with the intention of erecting another range of chambers above them."

A.P. Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology. Volume V (Text). London, 1889-1902, p. 16–17.

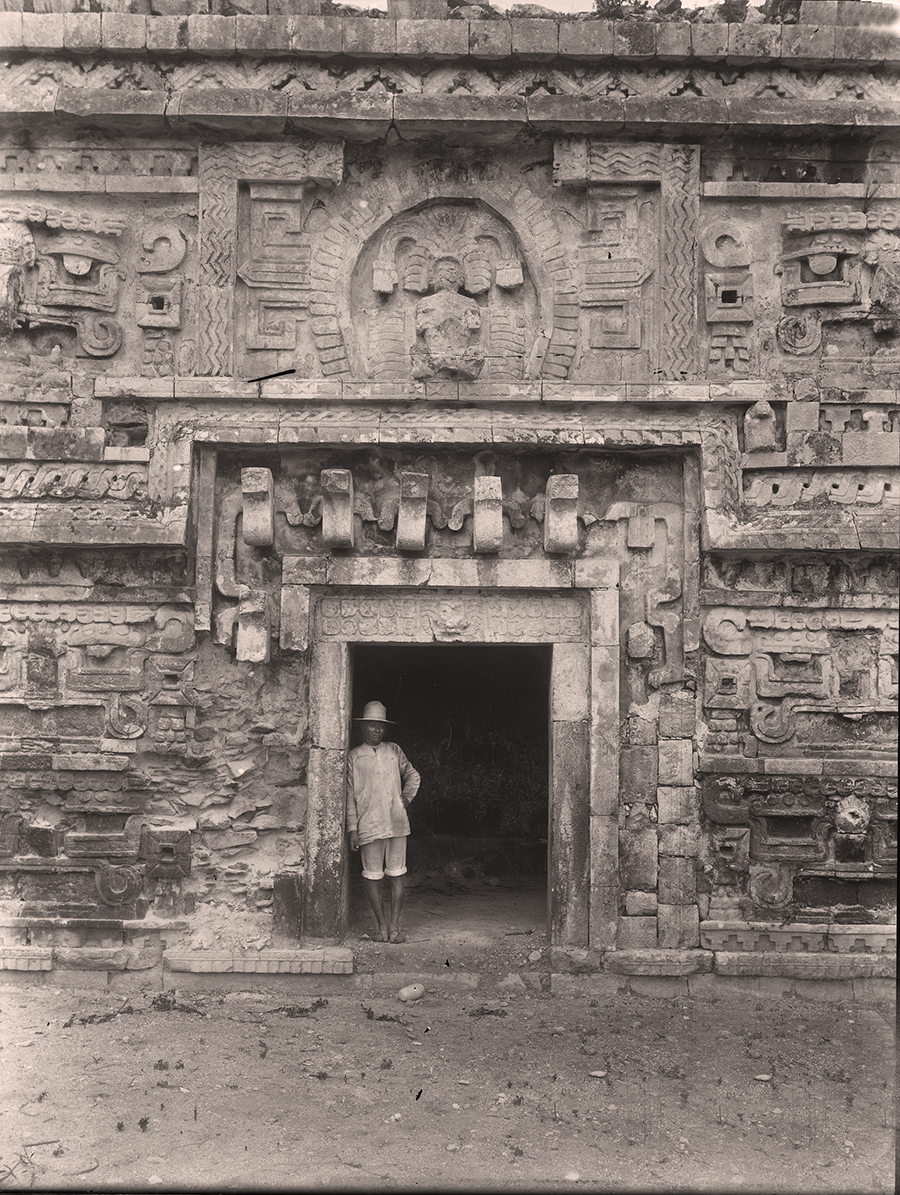

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

The façade of the East Wing is decorated in the Chenes Monster Mouth style, where a central doorway, surrounded by teeth, represents the open jaws of a monster. This mixture of Puuc and Chenes style is similar to the way Chenes imagery was incorporated into the Pyramid of the Magician at nearby Uxmal, although perhaps the quintessential Chenes monster mouth is Structure II at Chicanna.

On each side of the doorway, masks of long-nosed creatures appear in vertical stacks (unfortunately most of the long noses have broken off). Usually, such masks are assumed to represent the Rain God Chaac, but some scholars argue that they could just as well be Witz Mountain Monsters, representing the mountain caves out of which the Maize God was born. In any case, the East Annex walls and corners are completely covered by these masks except for the area above the doorway.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Photo from 2004 courtesy of Jeff Purcell

The figure seated crossed-legged in the circle above the door is similar to the seated rulers placed over doorways in the frieze of the Governor's Palace at Uxmal, with one interesting difference. At Uxmal, the figures sit at the center of eight serpent bars marked with glyphs pertaining to astronomical phenomena, while at Monjas, the ruler sits on top of a skyband marked with constellations signs. Unfortunately, most of the carvings on the skyband are difficult to make out, except for the "X" signs interspersed along its length.

Bruce Love. A Skyband with Constellations: Revisiting the Monjas East Wing at Chichen Itza. ONLINE RESOURCE (PDF)

Maudslay remarks that the straight-edged band marked with the wavy lines which indicate the body of the plume serpent bounds the sides of this design, and turns inwards at right angles over the top, and the two serpents' heads facing one another can with difficulty be made out just below the projecting cornice. Similar serpent heads at the ends of linear features can be more clearly seen at Uxmal (center of photo at the base of a stack of Chaac masks).

Remnants of the original red paint are still visible. The ruler himself wears an elaborate headdress of quetzal feathers, a feathered backrack, and a short cape over his shoulders.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

In the Maya Puuc architecture, palaces were often grouped around courtyards, as the raised platform plus the buildings and rooms that enclosed it was the functional unit of this architecture. Similar arrangements can be seen in the patio groups at the nearby Palace of Labná.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

The portion of the "basement" of Monjas seen on the right side of the previous photo is topped with long-nosed gods and royal mat patterns, but its undecorated lower walls offer a plain contrast to the baroque decoration of the Annex.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

Rain god masks with their long curved snouts overlook the passage between the east wing and La Iglasia. The geometric volutes patterning the medial molding of La Iglasia represent winds that accompany these rain gods.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

La Iglasia is a small one-room structure situated close to the Monjas Annex. It is in an exaggerated version of the Puuc Hills style, with plain walls and an oversized frieze and roof comb above. The frieze is decorated by Chac masks, the long-nosed rain god.

The consolidation work performed by John S. Bolles and his team at La Iglesia in Chichén Itzá during the 1930s had two primary objectives: structural stabilization and documentation. This was part of a larger project by the Carnegie Institution of Washington to excavate, study, and preserve Chichén Itzá during the first half of the 20th century.

More recently, Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) carried out further restoration between 2019 and 2020. The work aimed at further stabilization of the structure and preserving its heritage value.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial

Remarkably, the buildings in the older Puuc section of Chichén Itzá are little changed since Maudslay's visit in 1889, even considering the restoration and stabilization work done later. Puuc building techniques appear to be more sturdy than the later Toltec buildings and pyramids to the north even though the Puuc buildings were heavily ornamented with mosaic rain god masks and decorative moulding and complicated friezes.

The rickrack pattern in the molding below the roofcomb represented snakes, according to the Puuc Maya architectural vocabulary.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

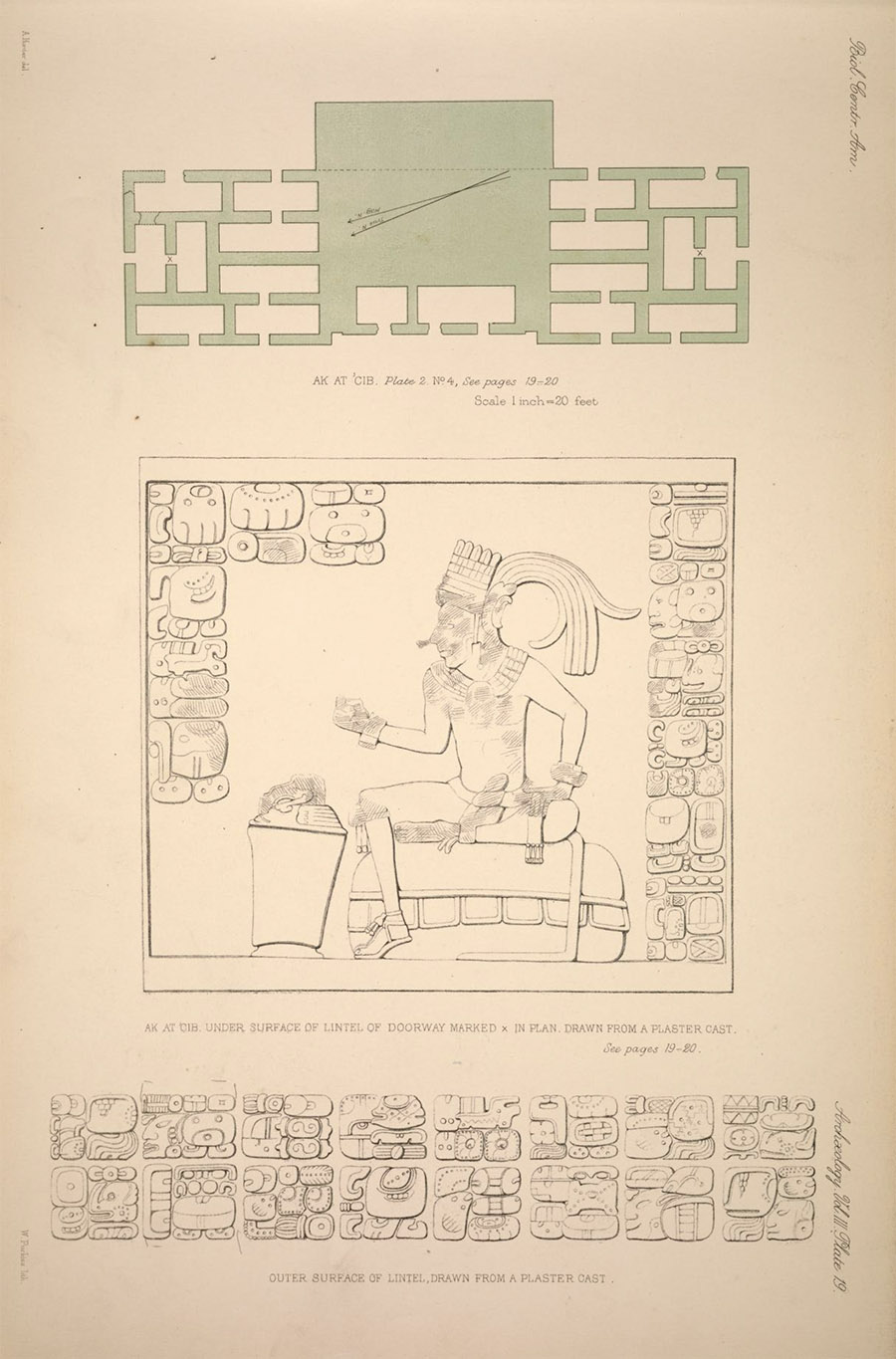

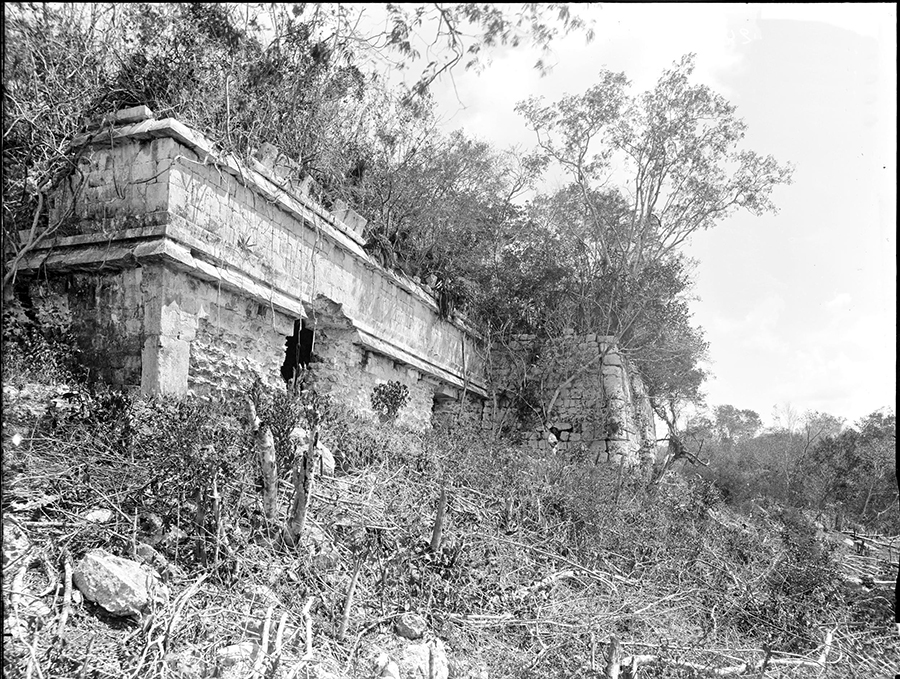

The modern nickname for this building, Akab Dzip, means "obscure writing" or "dark writing", so named because of a hieroglyphic text found written on a lintel over one of the inner doorways. The text itself includes a date of 870 A.D., most probably the dedication date of the building. Akab Dzip is about 100 feet along a trail from Las Monjas.

All the dates found on buildings in old Chichén are within 65 years of each other and range from 832 A.D. to 897 A.D., so 870 A.D. is near the midpoint of this era. These dates refer to the first phase of building at Chichén Itzá and are believed to be near the time when the city was founded.

A.P.Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, London: R.H. Porter. Vol. III (Plates), Plate 19, 1889-1902

It is believed that in its early days, Chichén was loosely governed by a triumverate of officials who were not hereditary rulers. For example, an inscription in Casa Colorado describes a fire ceremony presided over by three high officials, the highest of whom held the title Venerable Judge. This person, named Yahawal Cho' K'ak', was thought to have been the high head of the administration at Chichén Itzá.

"At the time when Chichén Itzá was founded, the office of k’ul kokom was held by Yahawal Cho' K’ak’. His personal abode was the Wa(k)wak Puh Ak Na, "the flat house with the excessive number of chambers" which is nicknamed Akab Dzib today. The name tells us that the Akab Dzib with its 18 rooms was considered a sumptuous mansion according to contemporary standards of the 9th century.

"Of the three individuals mentioned in the joint ceremony of the Casa Colorada text, only the kokom Yahawal Cho' K’ak’ is the possessor of such a house. K’ak’-u-pakal as well as Hun-pik-tok’ have not assigned any house or room under their names in or around Chichén Itzá. Considering all this and the central location at the East side of the Central Plaza of Chichén Itzá, the multiroomed abode, the venerable palace (u-k'ul otot) of Yahawal Cho' K’ak’ may in fact express the importance of his office."

Voss, Alexander W., and H. Juergen Kremer (2000), K'ak'-u-pakal, Hun-pik-tok' and the Kokom: The Political Organization of Chichén Itzá. In The Sacred and the Profane. Architecture and Identity in the Southern Maya Lowlands, 3rd European Maya Conference, University of Hamburg, November 1998, Pierre R. Colas et al. (eds), 149– 181. Acta Mesoamericana 10, Saurwein, Markt Schwaben. p. 7

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

The Akab Dzip is built in a rather plain classic Puuc style, with (once) smooth stone veneer topped by a simple frieze. It is believed that it was built in more than one phase, with the middle section being the oldest.

"The term kokom addresses the office of a supreme judge (oidor) obviously representing the highest administrative rank. The ah ts'ul wah is a military office. At the time when the Itsa controlled the city the office of k'ul kokom was occupied by Yahawal Choh K’ak’ closely assisted by the "supreme commander" of the military forces who was K’ak’-u-pakal. This man performed and controlled both secular and religious matters. This points toward a specialization within the elite at the top of the social hierarchy.

The third man was Hun-pik-tok', the k'ul tal(o) ahaw, i.e. the divine lord of Ek Balam. The use of an Emblem Glyph confirms a polity which retained the tradition of the Late Classic Southern Lowlands and adhered to the concept of divine rulership. The incorporation of Ek Balam's ruler into the government of Chichén Itzá was probably socio-politically motivated rather than a functional necessity.

The absence of kinship or other social relations between these three men gave way to the hypothesis that the controlling body of the political system at Chichén Itzá was solely based on mutual control and cooperation. The analysis gave way to the hypothesis that these men are related to the three lords who came to Yucatán from the West and established their rule at Chichén Itzá according to Landa's report."

Voss, Alexander W., and H. Juergen Kremer (2000), K'ak'-u-pakal, Hun-pik-tok' and the Kokom: The Political Organization of Chichén Itzá. In The Sacred and the Profane. Architecture and Identity in the Southern Maya Lowlands, 3rd European Maya Conference, University of Hamburg, November 1998, Pierre R. Colas et al. (eds), 149– 181. Acta Mesoamericana 10, Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.