The Great Temple of Kukulcán (the Feathered Serpent) at Chichén Itzá

Chichén Itzá was a dominant political, economic and religious force in the northern Yucatán from about 800 to 1000 A.D., and as such can be considered both a Terminal Classic (800-900 AD) and a Post Classic (900-1200 AD) Maya site.

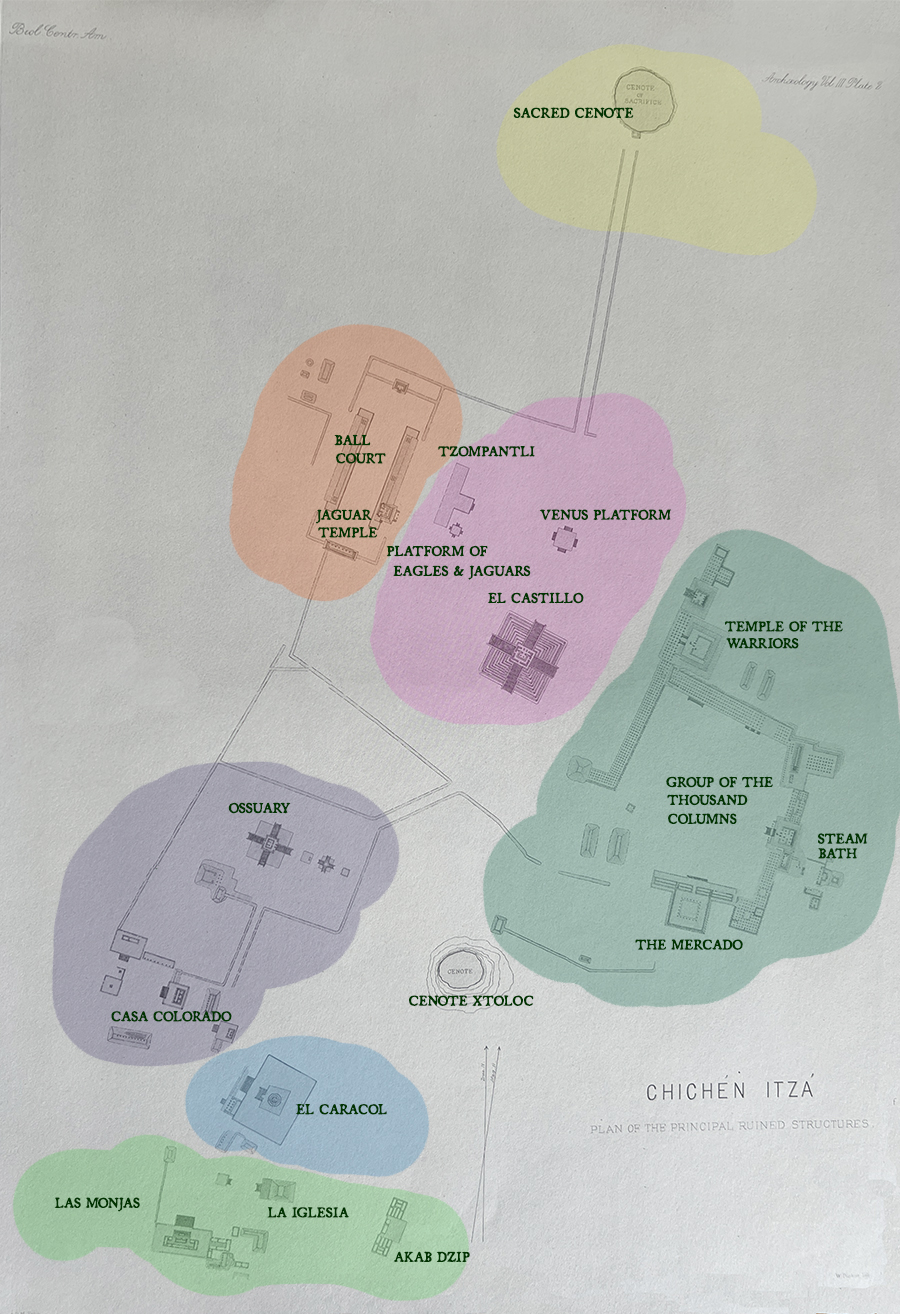

Chichén Itzá has two distinct architectural styles: the classic Maya Puuc Hills style of northern Yucatán, seen in the older southern part of the city and exemplified by Las Monjas, La Iglesia, Casa Colorado & Akab Dzip, and the Toltec style, representing a later non-Maya militaristic culture from central Mexico and exemplified by El Castillo, the Platform of Eagles & Jaguars, the Ball Court/Jaguar Temple, and the Temple of the Warriors.

The cult of Kukulkán/Quetzalcoatl was the first Mesoamerican religion to transcend the old Classic Period linguistic and ethnic division and is prominently represented in the later "Toltec" art of Chichén Itzá. This cult helped to unify disparate cultures, facilitating communication and trade by transcending old ethnic and linguistic divisions.

The history of Chichén Itzá is imperfectly understood, in part because of the scarcity of written inscriptions. Scholars disagree on when and how Toltec culture became dominant, some believing the Toltec conquered the city, while others maintain their influence came about by trade and peaceful cultural interaction. Complicating the story even further, legends tell of the arrival of the Itza, a highly Mexicanized group of Chontal or Putun Maya traders closely associated with the Toltec, with other Toltec groups following later.

Map adapted from Alfred Maudslay's Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Vol III, 1902.

Click on COLORED AREAS to view photos of major buidings and vistas from that area

Click here for an annotated Chichén Itzá reading list.

NEW! Subscribe to our free newsletter, MayaRuins Insights

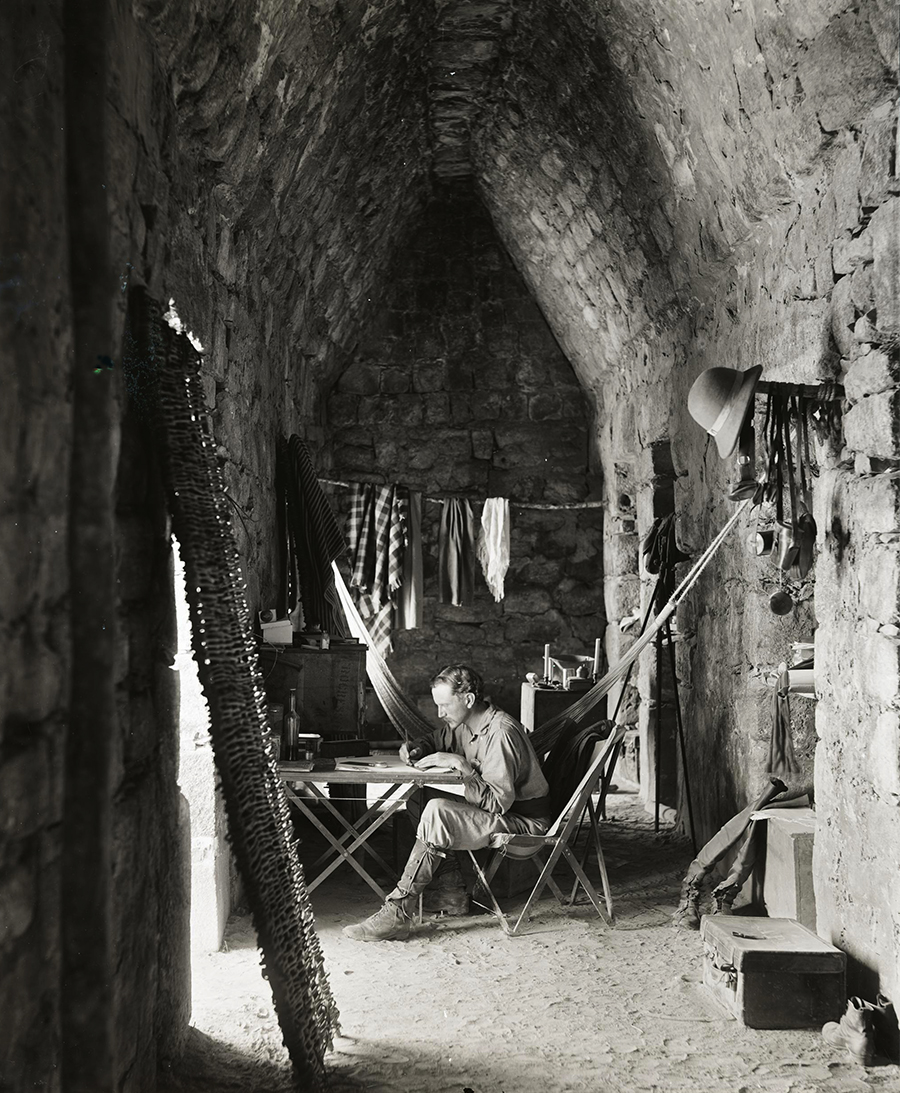

The majority of modern photos in this Chichén Itzá section were taken by Jeff Purcell on a 2004 trip to the Yucatán organized by Marion Canavan, with older photos of mine from 1993. These photos are supplemented and contrasted with Alfred Maudslay's glass plate negatives taken during his 1889 expedition and made available to the public through the courtesy of the British Museum.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Maudslay's photos give priceless insight into the unrestored state of Chichén Itzá before extensive archaeological reconstruction and restoration took place, and the wonderful "Alfred Maudslay and the Maya: A Biography by Ian Graham" gives color and context to the extraordinary work that Maudslay accomplished.

The photo above shows Maudslay in his quarters in the Monjas, which was high enough to catch the breezes and give a fine view. Maudslay writes: "To the southward where no clearing had yet been made, the sea of verdure spread unbroken from our feet. During the lovely tropical nights, when a gentle breeze swayed the tree-tops, and the moonlight rippled over the foliage, it seemed to be a real sea in motion below us, and one almost expected to feel the pulsation of ocean wave against the walls. In the daytime the woods were alive with birds; the beautiful motmots were so tame that they flew fearlessly in and out of our rooms, and the mocking-birds and scarlet cardinals poured forth a flood of melody such as I have never heard equalled."

Despite the above, however, Maudslay had a difficult time in Chichén Itzá: "During the month of May, we [Henry Sweet, Maudslay's esteemed assistant] were both ill with fever, but as our attacks fortunately occurred on alternate days we could each take it in turn to be nurse and patient." Graham continues the story:

"The fever left them both very weak, and as they were at that time entirely deserted by their workmen, they had the greatest difficulty in supplying themselves with firewood and water. Bringing a bucket of water up from the steep-sided Xtoloc cenote, then across 400 yards of level ground and up the steep and partially dislocated stairway of the Monjas was an ordeal requiring frequent rests along the way. Fortunately by dosing themselves with quinine both men recovered and were able to resume work, although they still felt very feeble for many days."

Ian Graham. Alfred Maudslay and the Maya: A Biography by Ian Graham, University of Oklahoma Press. Norman and London 2002, p. 162-163