1. The Ossuary or High Priest's Grave is built over an earlier temple & a cenote

The name "High Priest's Grave" was given to this structure by Edward Thompson

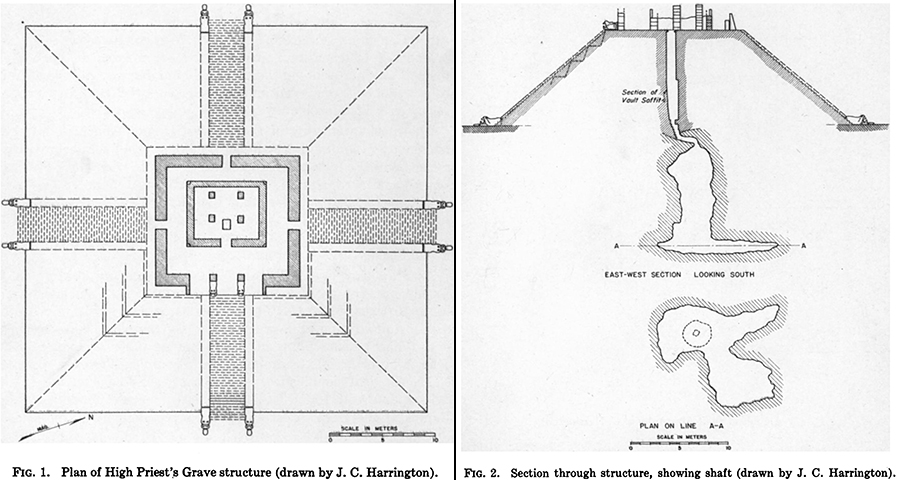

The Ossuary is built over a deep cave and cenote, which the Maya believed to be entrances into the underworld. The pyramid itself has nine levels, which reflects the number of levels in the underworld. Several graves were found at the entrance to the cavern beneath the pyramid.

The temple on top of the pyramid has an air intake column and vertical passageway leading to the underground cave and cenote, and is significant to the agricultural calendar because, at the beginning of the rainy season, the sun enters the vertical passageway and illuminates the floor of the cave 10 meters below, renewing the earth. Several rich offerings were found on the floor of the cave at this location.

Maudslay observed nearly a century and a half ago that the ground plan around the Olssuary bears a very marked resemblance to that of the later Castillo, as do the design and orientation of the temples themselves. Both temples are oriented toward the east and have four stairways each, flanked by balustrades carved with serpents leading to a temple at the top, and both main temple entrances display dual snake columns which once held up lintels and temple walls.

In regards to the temples' ground plans, each temple rests on a plaza large enough to accomodate huge crowds, is bounded by low walls and fed by ceremonial "sac beys" or roads funneling into their plazas, and each is supplied with a Venus Platform, a raised stage for the performance of public dance and ritual. It is interesting to think that the Olssuary area might have been a prototype for the later and larger Temple of Kukulcan (El Castillo) and its surroundings.

Thompson, Edward H., and J. Eric Thompson. “THE HIGH PRIEST’S GRAVE: CHICHEN ITZA, YUCATAN, MEXICO.” Publications of the Field Museum of Natural History. Anthropological Series, vol. 27, no. 1, 1938, pp. 1–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29782228. Accessed 6 Sept. 2025.

Edward Thompson was the first archaeologist to have himself lowered into the cenote over which the temple was built. He writes: "The next day was spent in arranging for the descent, and the following day I was let down by means of a rope and blocks into the pit. My previous experience in subterranean chambers had familiarized me with this class of work. The clear flame of my lantern relieved me of any fear of mephitic air, and with my keen bowie knife between my teeth ready for instant use, and lighted lantern in one hand, I examined the walls of the pit as I went down. The pit seemed to be in part the work of nature, but greatly changed and enlarged by the work of the ancient people.

"...I touched bottom upon a heap of earth near the center of the chamber and directly under the orifice where the candlelights of my anxious boys gleamed like stars above me. I sent up a reassuring call that all was well and commenced my investigations. My brush had hardly raised dust when I found that my expectations were to be realized. A bead of jade over five inches in circumference, beautifully formed and so polished that it gleamed under the light of my lantern, was right at my feet, and close beside was a beautiful jade amulet. A little to one side were fragments of a vase, the like of which has never been dreamed of as belonging to this people. Not large, but made of a translucent mineral very much resembling alabaster, its artistic finish and general appearance make it easily the finest gem of the class ever found in Yucatan."

Thompson, Edward H., and J. Eric Thompson. “THE HIGH PRIEST’S GRAVE: CHICHEN ITZA, YUCATAN, MEXICO.” Publications of the Field Museum of Natural History. Anthropological Series, vol. 27, no. 1, 1938, pp. 1–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29782228. Accessed 6 Sept. 2025, p. 29

While mapping the shaft in 1936, J.C. Harrington found part of the vault of an earlier temple and thus demonstrated that this pyramid was built on top of an earlier temple. It is worth noting that buried temples are similarly enclosed within the pyramidal substructures of the Castillo and Temple of the Warriors. Both of these temples belong to the initial building phase of the city and are classed with the "Old Chichen" structures to the south.

Harrison himself, in a later review, wryly recalls: "Many years ago the reviewer allowed himself to be lowered by two monolingual Mayans to the bottom of the subterranean cavern under the High Priest's Grave at Chichen Itza, having prepared for the exploit by memorizing the Maya words for up and down."

Harrington, J. C. American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 58, no. 2, 1954, pp. 183–84. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/500139. Accessed 7 Sept. 2025.

NOTE: the entrance to the shaft leading to the underground cave and cenote is the small square in front of the entrance to the inner temple in the diagram on the left.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

The ground level serpent heads and the base of the central stair plus some of the balustrade depicting the intertwining serpent bodies was intact when Maudslay photographed it in 1889, as was a good bit of the walls of the upper temple. However, the veneer cladding of the pyramid was in rubble, having been loosened by tree roots and other vegitation.

It is interesting that the rattlesnake tail a little to the left in the photo was still in the same position when we visited in 2004.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

The feathered serpent heads and columns guarding the entrance of the temple as they appeared in 1889. This entrance led to an inner ambulatory which surrounded the temple proper.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

This photo better shows the pattern of intertwined serpent bodies decorating the ascending balustrades bordering the staircase.

In addition to the serpents decorating the balustrade, and those that once held up the central lintel over the entrance to the temple ambulatory surrounding the inner temple, eight interlocked serpents also circle the top perimeter of the upper pyramid. The open-mouthed head of one of these serpents can be seen in the upper left tier of the pyramid. It is said that four of these serpents were once decorated with turquoise discs, turquoise being especially significant in the battle dress of Toltec warriors, while the other four were decorated with ear rings.

Thompson, Edward H., and J. Eric Thompson. “THE HIGH PRIEST’S GRAVE: CHICHEN ITZA, YUCATAN, MEXICO.” Publications of the Field Museum of Natural History. Anthropological Series, vol. 27, no. 1, 1938, pp. 1–64. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29782228. Accessed 6 Sept. 2025, p. 25.

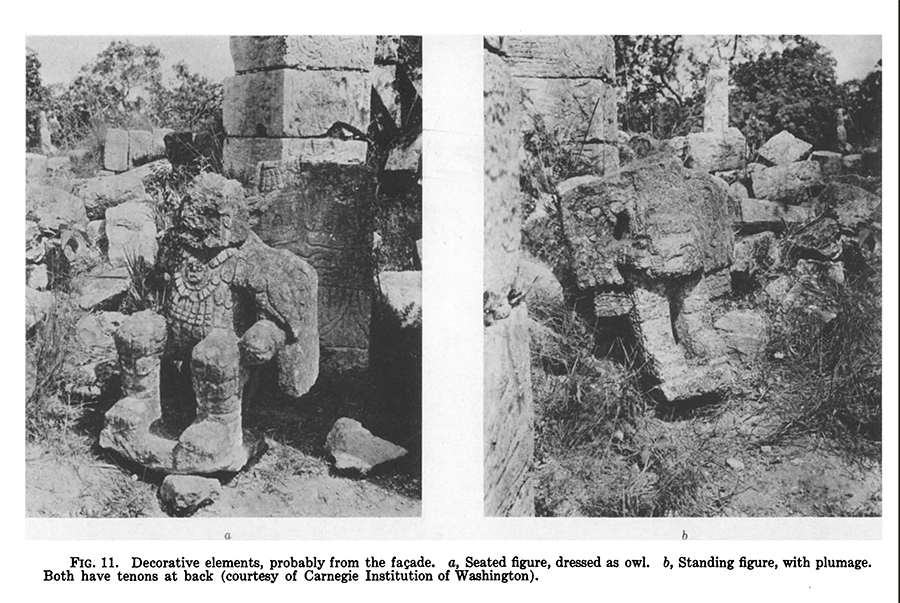

The façade of the temple was probably decorated with different bas reliefs and tenoned sculptures of snakes, birdmen (shown here), men with god-like masks, etc. There are also inscriptions dating from 894 A.D. on temple pillars.

In addition, the pyramid itself was decorated with carved panels showing fruit, cocoa beans, jewels and animals, all images of the rich fertility of the earth.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

This corner of a wall was once part of the temple atop the pyramid. The masks of the rain god Chaak on the corner is characteristic of the older regional Puuc style found in the southern part of the site called "Old Chichén Itzá".

The pyramid was later modified or rebuilt in the Toltec style, with carved feathered serpents adorning the staircase and the pyramid itself similar to the larger and newer El Castillo (Temple of Kukulkan).

This mix of influences makes the Ossuary a transitional structure reflecting cultural shifts occurring at the site during its main growth period. A recent study of charcoal found in the shaft beneath the Ossuary suggests an initial construction phase occurred in the early 8th century A.D., before the Toltec-style remodelling which was commemorated by a pillar placed in the temple and dated A.D. 998:

"In the archaeological literature, the Osario at Chichén Itzá has been defined by the 998 A.D. long-count date inscribed on a pillar at the top of the pyramid. Although the pillar could have been added long after the construction of the pyramid, the complex is, nevertheless, consistently treated as a late construction. From the outset, this has been problematic. J.C. Harrington, who mapped the Osario, the shaft, and the cave in the 1920s, discovered the soffit of a vault behind the stones of the shaft suggesting that a vaulted structure stood on the stone platform at the base of the shaft before the pyramid was built. An investigation of the Osario by the Gran Acuífero Maya project collected charcoal from the shaft and the cave. Radiocarbon dating establishes that the earlier structure was terminated and the Osario pyramid was constructed in the early eighth century A.D. Thus, the Osario predates the Castillo."

Recent Radiocarbon Dates from the Shaft and Cave under the Osario at Chichén Itzá: Rethinking the High Priest's Grave. Melanie Saldana, James Brady. Presented at The 84th Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Albuquerque, NM. 2019 ( tDAR id: 451105)

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

Profile view of the Chaak rain god masks in the foreground, while in the background some of the decorative panels on the upper tiers of the pyramid are faintly visible.

NOTE:The top three tiers of the pyramid seen in the background had decorative panels showing fruit, birds, animals, and cocoa beans. These panels can be made out faintly in the photo, as can a feathered serpent at the base of the staircase and another one in profile at the top corner of the pyramid.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

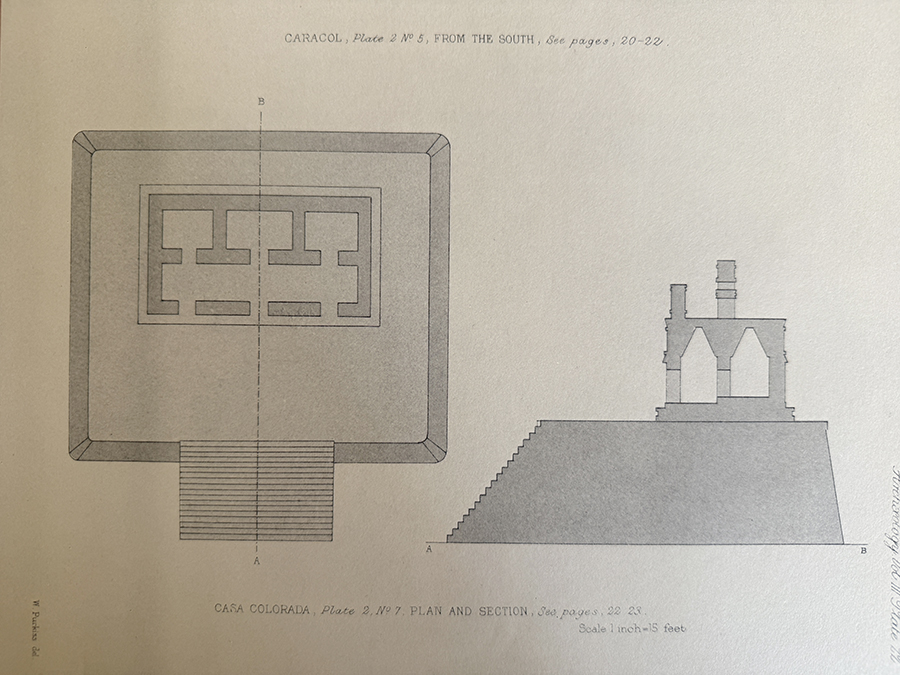

The Casa Colorado is a restrained and formal example of the Puuc style and is located adjacent to the plaza where the Ossuary stands. It is characterized by plain lower walls and an upper façade decorated with mosaic stone patterns. For a more extravagant expression of the Puuc style, see the Iglesia building in Old Chichén further south.

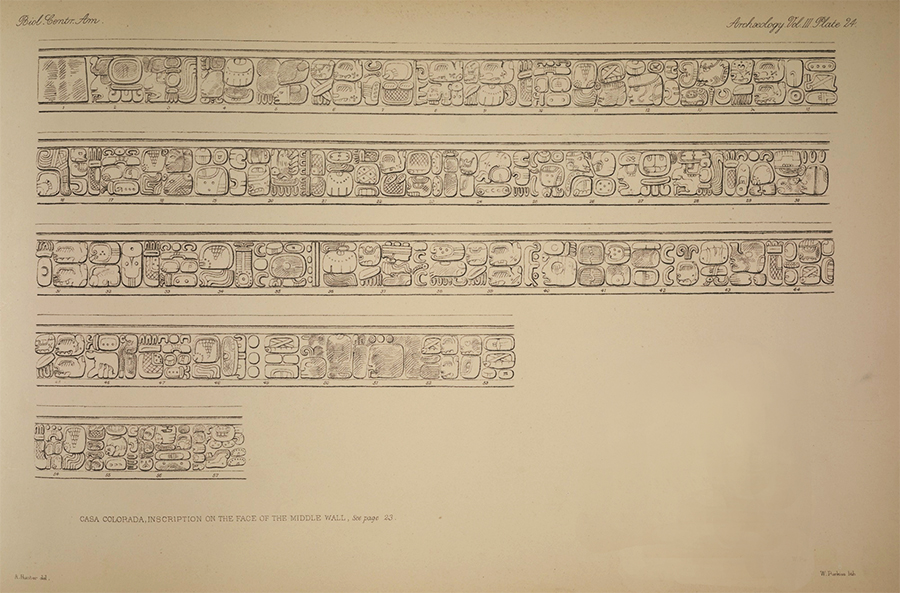

A significant panel of glyphic inscriptions was found above the doors on the inner wall of this building. It describes the participants in four fire ceremonies which took place in this building around the time when the city was founded.

A.P.Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, London: R.H. Porter. Vol. III (Plates), Plate 2 No. 5, 1889-1902

The text state that the fire ceremonies took place in a period of two years early in the history of Chicnén Itzá, within the precincts of Casa Colorado.

In the article "New Drawings of the Casa Colorada Text, Chichen Itza, Yucatan" by Bruce Love, there is a fascinating modern photo of the Casa Colorada glyph band in situ. Due to their age (circa 870 A.D.), the glyphs are somewhat eroded, so this article documents the efforts, using modern methods, to preserve the most accurate possible representation of the inscriptions.

A.P.Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, London: R.H. Porter. Vol. III (Plates), Plate 24, 1889-1902

This text records four fire rituals which took place from September 11, 869 to December 12, 871 A.D., early in Chichén Itzá's history. The text also names the three officials who performed these rituals, all of whom are known from other inscriptions at Chichén Itzá: K’ak’-u-pakal, Hun-pik-tok’, and, the highest ranking individual, Yahawal Cho' K’ak’, who is referred to only by his title, k'ul kokom

"From this it appears that notwithstanding the functional role of the other individuals mentioned in the Casa Colorada text, the ultimate responsibility for this type of public affair at Chichén Itzá rested with three persons who occupied three distinct offices which possibly represented the top of the government."

Voss, Alexander W., and H. Juergen Kremer (2000), K'ak'-u-pakal, Hun-pik-tok' and the Kokom: The Political Organization of Chichén Itzá. In The Sacred and the Profane. Architecture and Identity in the Southern Maya Lowlands, 3rd European Maya Conference, University of Hamburg, November 1998, Pierre R. Colas et al. (eds), 149– 181. Acta Mesoamericana 10, Saurwein, Markt Schwaben, p. 6-7.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

The faint buildings of the Monjas can be seen in the extreme right midground of this photo.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.