The East Group is dominated by the Temple of Warriors and 1000 Warrior Columns

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

When Alfred P. Maudslay was working at Chichén Itzá in 1889, he termed this group "The East Group". The large grassy area in the foreground was able to accomodate truly massive crowds for public ritual and ceremony.

In this photo, the Temple of the Warriors is at center, with the smaller Temple of the Tables to the left and the Group of 1000 Columns on the right, partially out of frame & obscured by trees. The Mercado is to the upper right and outside the photo.

Map adapted from Alfred Maudslay's Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Vol III, 1902.

Please click on SMALL GREEN LABELS to link to structures, or keep scrolling to see all photos

Click here for an annotated Chichén Itzá reading list.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

The Temple of the Warriors gets its name from the arrays of columns carved to represent Toltec warriors which surround and extend from its base.

The frieze of the temple which rises atop the pyramid is decorated on the corners and center with long-nosed rain god masks interspaced with vision serpents opening to reveal human heads. These elements are typical of the Maya Puuc architecture of the region: similar examples can be seen at Uxmal, Labna and elsewhere.

A Chac Mool stands in from of the central entrance, while behind it two giant serpent columns like those seen in El Castillo and the Upper Temple of the Jaguars raise rattlesnake tails which once supported wooden lintels over the doorway. These elements are are associated with the cult of the feathered serpent, Kukulcán/Quetzalcoatl, and with the Toltec style influenced by non-Maya militaristic culture from central Mexico.

Alfred Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Vol III & IV: Plates. London, 1889–1902, Plate 60.

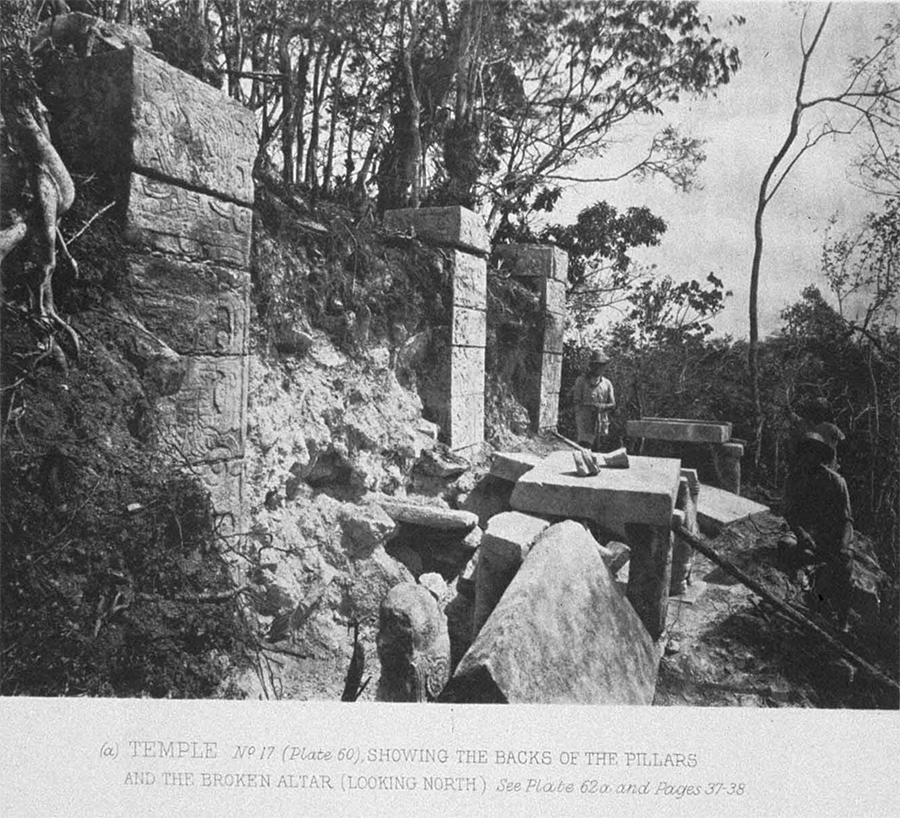

Fragments of feathered serpent tails which once held up the temple rafters were scattered over the sides of the pyramid at the time of Maudslay's visit. A Chac Mool which stood in front of the temple lay headless, and giant carved blocks which once composed the temple columns lay in disarray. This is Maudslay's photo of the western terrace of the pyramid as he found it.

Maudslay remarked that the Temple was found in the same decrepit condition as the Temple of the Tables, but that it must have supported one of the principal buidings in the city.

Continuing his description of the state of the temple at the time of his visit, he writes: "Two stairways with a smooth slope between them...lead to a broad terrace, in the centre of which is a broken recumbent stone figure. Another short stairway must have led from this terrace to the temple, the doorway of which was adorned with two serpent columns; portions of these columns and the two huge rattlesnake capitals lie scattered over the slope and the terrace below.

The floor of the temple is 45 feet above the level of the ground. The remains of square columns and the indications of partition-walls can just be made out. This building would probably well repay excavation, as the back wall must be entire to the height of a few feet, and it is more than possible that all the figures of an altar similar to that last described (Temple of the Tables) would be found."

Alfred Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Vol V: Text. London, 1889–1902, p. 38

This famous photo is property of Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Gobierno de México, and is being used here for non-comercial purposes.

The Chac Mool has been restored to its position in front of the entrance to the temple and has had his head reattached. He holds an offering plate on his stomach. Behind him, two massive rattlesnake columns raise their tails to support what probably was a wooden lintel spanning the entrance to the temple. In the background, small Atlantian figures support an altar similar to that found in the Temple of the Tables.

Two giant serpent columns dominate the temple atop the pyramid, with square columns carved to represent Toltec warriors standing behind them. Rain God snouts are silhouetted against the sky on the corner right wall.

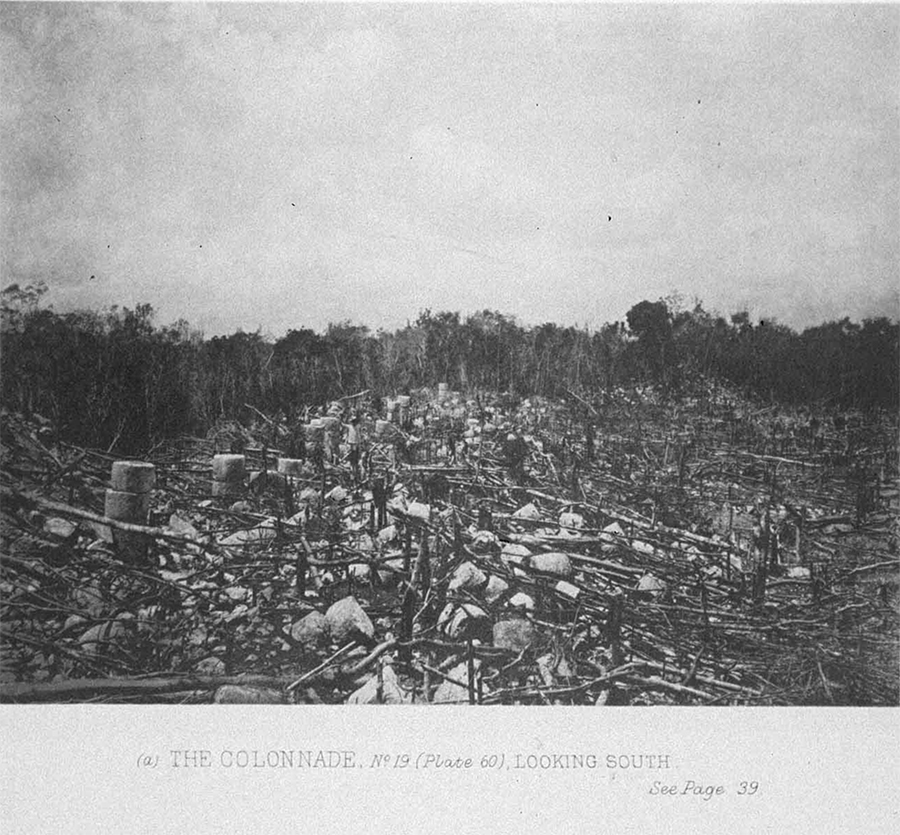

Maudslay writes: "On a raised terrace in front [at ground level] can be traced the remains of 64 square columns in four rows of sixteen each. I was unable to ascertain if these columns had supported a stone roof, for although many roofing-stones are lying among the débris, these have more probably fallen from the building above. "

Alfred Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Vol V: Text. London, 1889–1902, p. 38

On the left, a low wall separates the Temple of the Warriors from the adjacent Temple of the Tables. At the top of the left balustrade flanking the central stair, a serpent head can be discerned, while a small figure holding a bowl stands above, possibly holding an oil container supporting a flame torch. These balustrades also once supported standard-bearers which held flags and pennants for display on ceremonial occasions.

At the top of the balustrade is an open-mouthed serpent head. Above the serpent is a small figure holding a bowl which might have been used as a oil torch. Beyond that can be seen the top of the rattle of a serpent tail used to hold up wooden lintels.

The square columns at the base of the temple were carved and painted to represent armed Toltec warriors and possibly supported a roof or small open patio.

These warriors wore full battle dress and carry spears and shields. They wear headdresses of green quetzal feathers. These columns were originally painted in bright colors, and traces of paint can still be seen (the original colors of Toltec battle gear are approximated in this British Museum panel).

The warrior's face on the front column can be seen in the fourth block from the top, facing to the right with his arm holding a shield.

I am intrigued by the befeathered little figure at the base of this column, with a song scroll or speech scroll coming out of his mouth. Similar figures are carved on the bottom block of all the pillars in front of the Temple of the Warriors (see previous photo).

Also interesting are the puffy ankle and knee ornaments the warrior figure in the upper block wears. Could these be eagle feathers? Could these columns be representing the Eagle and Jaguar Orders of the Chichén Itzá military? Here is a similar costume from the Sculptured Chamber of the Ballcourt showing Toltec warriors in battle dress. The central warrior also wears this ankle and knee gear.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

This warrior's girdle has spots and a tail hanging behind, so he appears to be wearing a jaguar pelt. Look for the hand and waist in the third block from the bottom to locate the pelt, with a tail extending into the lower block.

Perhaps this warrior is a member of the Order of Jaguars, one of the two main military groups at Chichén Itzá, the other being the Orders of Eagles. These carvings seem to depict uniforms and insignia which indicate group membership.

In his report of his 1889 expedition to Chichén Itzá, Maudslay wrote:

"The next structure (No. 17) did not at first promise to repay for any time expended on its examination; it appeared to be merely a lofty mound of loose stones and rubbish with steep sides, very dangerous to clamber over.

"However, two large serpents' heads at the foot of the slope on the west side and traces of steps showed that it had once been ascended by a fine stairway. Then my attention was attracted by a large rattlesnake capital lying near the foot of the mound..."

A.P. Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology Vol V: Text. London 1889-1902, p.37.

Alfred Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Vol III & IV: Plates. London, 1889–1902, Plate 60.

Maudslay continues: "Lying near the foot of the slope on the east side of the mound I had seen two of the squat grotesque figures with their arms raised, as though intended to support a weight, which are figured in one of Dr. Le Plongeon's publications; and whilst clambering over the steep slope on the same side I found the heads and hands of similar figures sticking out from amongst the loose stones, and finally I was able to make out that a double line of these figures had supported some broad stone slabs. All their faces had been turned inward towards the temple, but the purpose of the slabs and their caryatid-like supports was altogether a mystery to me; however I had not sufficient labourers at the time to commence an excavation, and I had unwillingly to postpone any attempt to gain further information.

"It was not until the last week of my stay that I was able to commence work on this mound, and as time was very short we began excavation where the grotesque little figures had attracted my attention. We succeeded in laying bare the whole of the east faces of the sculptured columns, of which only the top stones were previously visible, and they proved to be 9 feet high. It was found that the foundations of the side walls of the building had extended beyond the two lines of figures and the slabs which they supported, but that no trace of the back wall remained; it had disappeared completely, and must now form part of the broken stone and rubbish covering the slope of the mound. The whole of the interior of the chambers up to the height of the tops of the columns, that is to say for 9 feet, is filled up with the fallen roof and superstructure, and out of this mass trees of considerable size are now growing.

"...The slabs supported by the grotesque little caryatids must have formed an altar running all along the back of the inner chamber, and parts of it are well shown in the photographs."

A.P. Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology Vol V: Text. London 1889-1902, p.38.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Schele writes: "Augustus Le Plongeon, an eccentric early explorer, photographed an altar in the shape of a square table mounted on fifteen atlantean figures set in three rows of five. Fortunately, the English artist Adela Breton recorded all of the legs and the carved tabletop in water color drawings in 1902. Shortly after her visit to the site, archaeologists moved the legs to Mexico City.Today some of them can be seen in the Museum of Anthropology". Perhaps unknown to Schele, Maudslay also made this glass negative photos of the table in 1889.

This table sat in the outer chamber in front of the door that leads into the inner sanctum. Priests probably used it to hold braziers and food offerings for the ceremonies that took place in the temple. The top of the table depicted warrior-ballplayers entwined with a Feathered and Mosaic Serpent.

Each of the firgures on the legs wore different face and body decorations. Schele continues: "We do not know the meanings of these different face and body decorations, but we have the distinct impression we are looking at uniforms...We suspect these fifteen figures represent a set of specific offices and ritual functions in the Itza state."

Linda Schele & Peter Mathews. The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs. Simon & Schuster. New York, 1998, p. 241

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

This building originally had a roof, possibly thatched, upheld by columns and pillars with bas–reliefs of warriors on the front. It had four accesses: two in front with communicate with the Plaza and two side ones which link up with the Temple of the Warriors and the North-Eastern Colonnade.

In the interior, a stone bench runs along the entire length of the building. There is also an altar with sculpted figures undertaking a ceremony with incense offerings.

From INAH (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia) sign at the site

Maudslay had to hire workmen to clear the jungle in order to photograph the ruins. The arduous job of reassembling the columns fell to later archaeologists.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

The North Colonnade can be seen as the very long array of pillars extending back and to the right of this photo. It had two main entrances to the courtyard of the Group of One Thousand Columns, plus two side exits one of which led to the plaza in front of the Temple of the Warriors. Steps leading down into the Warrior' plaza can be seen against the right side of the Temple toward the front.

The pedestal of the Northern Colonnade is decorated with a bas-relief of eagles and jaguars devouring hearts. This photo shows a jaguar holding a human heart in his paw, surrounded by spears. The upper panel has swirls of feathers belonging to a feathered serpent.

This stair is the entrance to the so-called "Mercado" and leads up to a terrace which is about 5 feet higher than the ground outside the wall. At the back of the terrace there are the remains of four double-chambered houses and a passage leading to a courtyard ringed with columns.

The name El Mercado (the market) is a fanciful name given in modern times. There is absolutely no evidence that this area was ever used as a market or space for commerce in ancient Chichén Itzá.

Intricate carvings grace many of the the walls of Chichén Itzá. This particular wall is near stairway which serves as an entrance to El Mercado. The top level shows two feathered serpents facing each other with their bodies undulating outwards from the center.

The bottom panels present elaborately dressed warriors wearing opulent quetzal feathers and holding a connecting rope. From their mouths "Speech Scrolls" or "Song Scrolls" are emitted. The middle bottom panel even shows a speech scroll decorated with flowers. This looks to me like a celebratory procession with singing and dancing performed under the auspices of the feathered serpent.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

Maudslay writes: "The floor of this court is about 5 feet higher than the ground outside the walls...the square depression in the centre of the court, marked with a dotted line, was surrounded by columns which measured 14 feet in height, including the the capital. The corner colummns are the larger, each measuring 2 feet 2 inches across; the diameter of the others is 1 foot 9 inches. All the columns have fallen. There is not much débris in the court, and the height of the columns, their distance from the walls (24 feet), and the fact that the wall where it is 18 feet in height shows no signs of the spring of a vault, altogether precludes the possibility of those columns having supported a stone roof.

"Although I have already stated that it was very probable that some of the colonnades were roofed with wood and cement, No. 30 [this courtyard] affords the ony example I have met with where it can be confidently asserted that some material other than stone must of necessity have been used for roofing. It seems most probable that wooden architraves connected the columns, and that beams sloping downwards from the outside walls rested on these architraves, the central patio being left open. The interstices between the beams were probably filled with rubble and cement, as in the modern houses in the Spanish-American towns."

A.P. Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology Vol V: Text. London 1889-1902, p. 42

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell