Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

The view from El Castillo gives an impression of the massive size of the Ballcourt complex, the largest in Mesoamerica. The ballcourt measures 545 ft long by 225 feet wide.

In the middle foreground is the Upper Temple of the Jaguars sitting atop the eastern ballcourt wall and facing inward, with the Lower Temple facing outward. To the left is the Temple of the Bearded Man, while the opposite small Temple C is obscured by the shrubbery.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

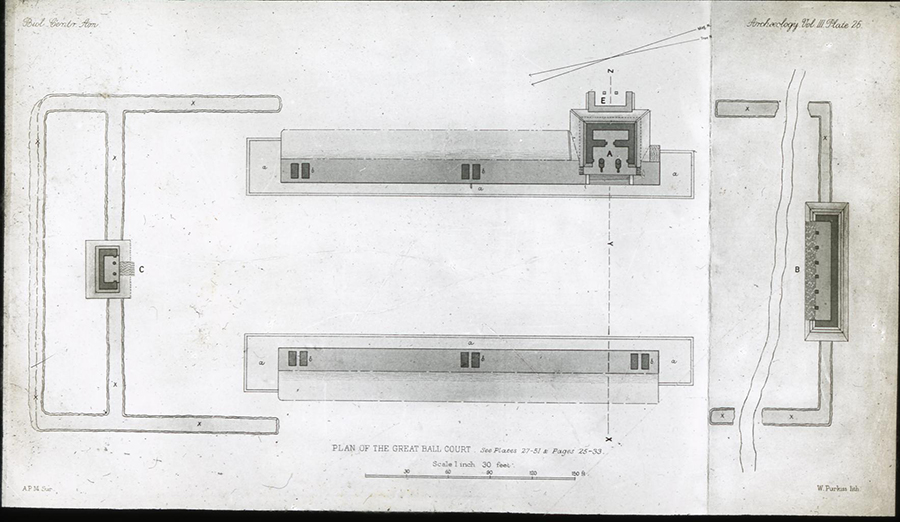

Maudslay's drawing shows the four temples of the ballcourt complex: Temple A (Upper Temple of the Jaguars which faces into the ballourt), and Temple E (Lower Temple of the Jaguars facing outward from the ballcourt), and End Temples B & C.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

This photo, taken from Temple B, looks along the playing alley of the ballcourt toward the small Temple C. It is said that the acoustics are such that a whisper from Temple C can be clearly heard at Temple B.

The ruined Jaguar Temple can be seen perched atop the ballcourt wall on the left.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Because of its damaged condition, this photo reveals the interior design of the Upper Temple of the Jaguars. It was constructed as two parallel vaulted galleries with a doorway separating the outer and inner sanctum.

In front are portions of two serpent columns that once held up the façade. The front half of the outer gallery has fallen into the rubble heap below, onto the ballourt floor.

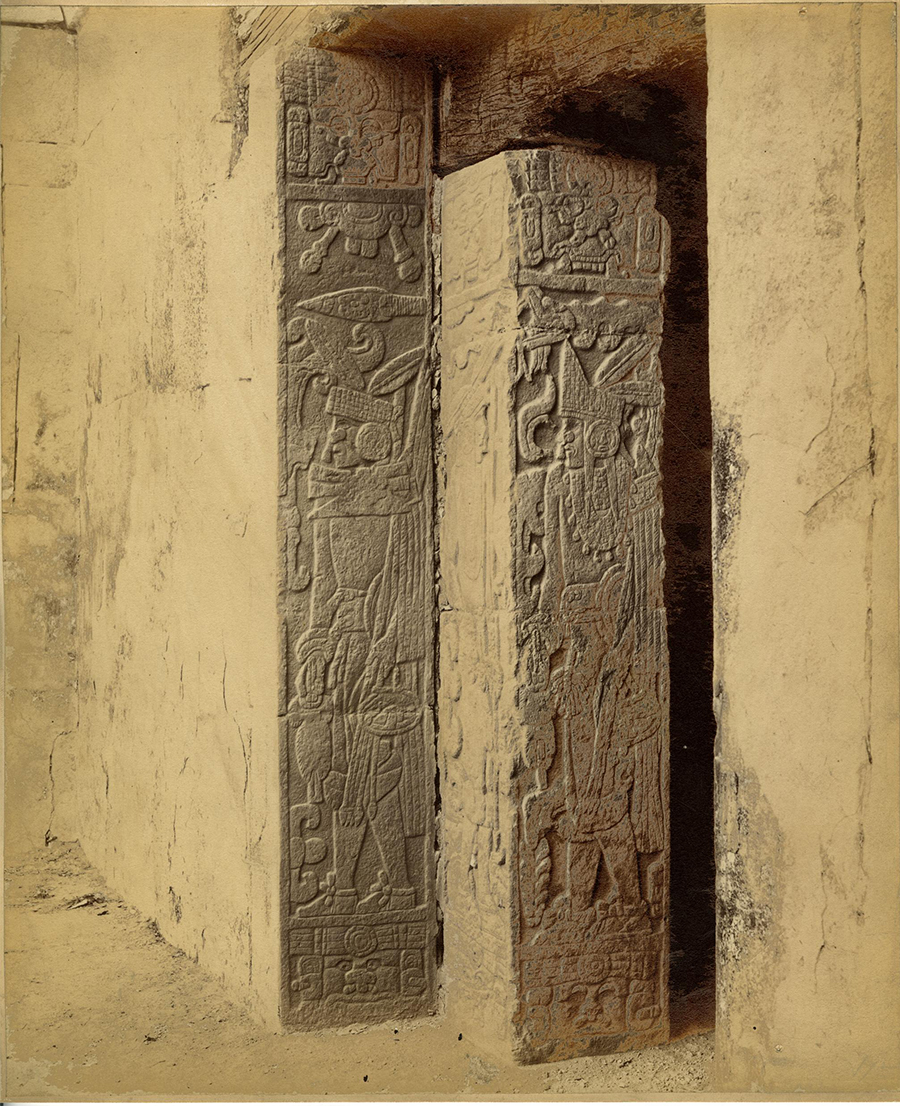

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

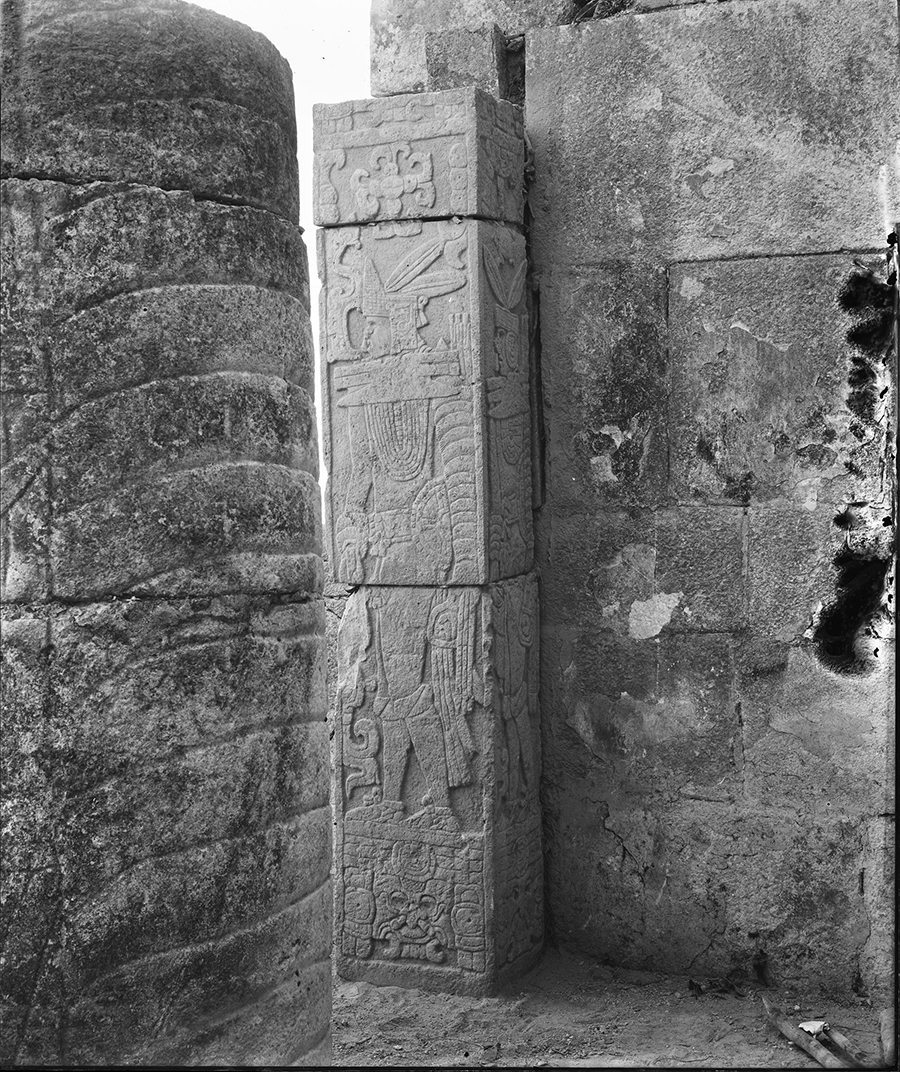

This column represents a feathered serpent, with short feathers on its head, longer feathers on the side, and scales in back. The serpent has a typically Maya superorbital plate and a small curly tongue. Fangs show through its open mouth.

Behind the serpent column are carved rectangular doorjambs that once defined and held up the sides of the temple. In his Maudslay biography, the archaeologist Ian Graham points out:

"Maudslay can be credited with several specific contributions to knowledge of Chichén Itzá architecture. One concerns the serpent-columns found at the entrance to the upper ball–court temple and in other buildings: large stone serpent-heads are set at the foot of the columns, but in all cases the capitals and portions of the façade supported by them had fallen.

"Maudslay found broken stones carved to represent rattlesnake tails, and these he was able to show had each formed one limb of an L-shaped capital, set with the rattle turned upward — a feature missed by the archaeologist W.H. Holmes, usually a careful observer.

"Such observations added to the accuracy of the reconstruction drawings which he afterwards had an artist prepare of a few buildings, including the upper temple of the ball–court."

Ian Graham. Alfred Maudslay and the Maya: A Biography by Ian Graham. University of Oklahoma Press published by special arrangement with The British Museum Press, London. 2002, p. 163–4

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

This is a ballcourt ring found broken off from the ballcourt wall and fallen into the playing alley below. Maudslay's drawing suggested it be reattached to the ballcourt wall. This photo gives an excellent sense of the huge size of these ballcourt rings.

This ballcourt ring shows two entwined feathered serpents with heads facing each other at the top of the ring. Legend holds that if a player propelled the ball through the ring, it would emerge in Xibalba, the Mayan underworld.

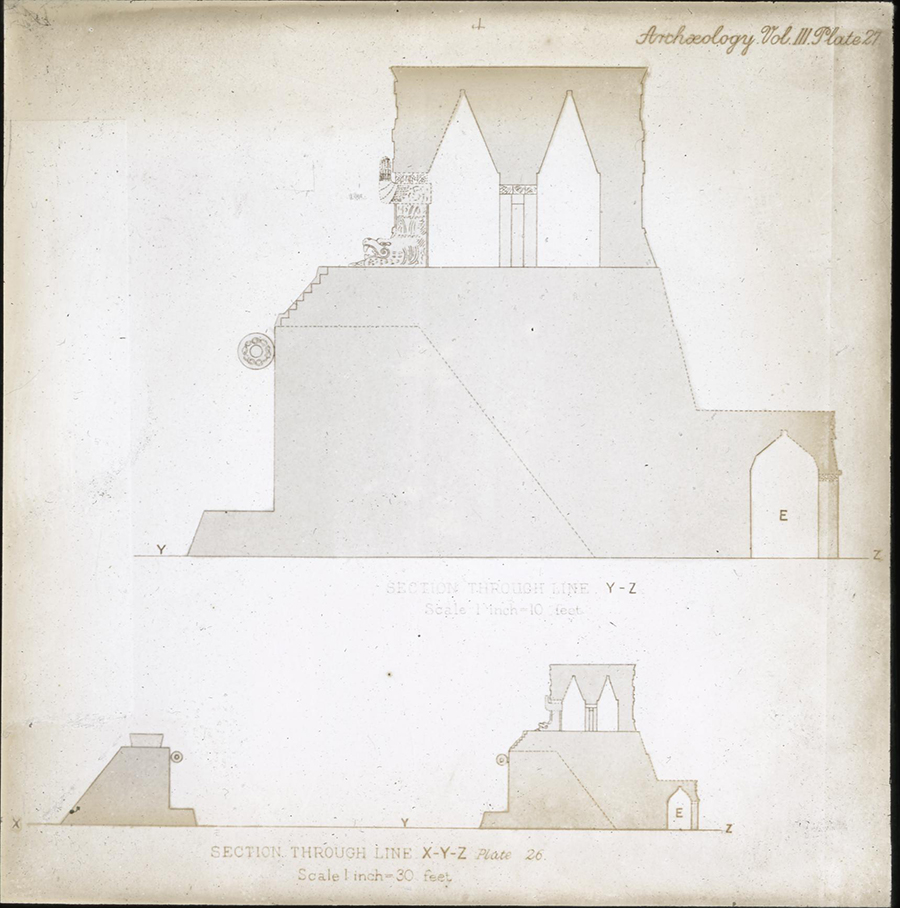

These drawings represent Maudslay's recommendations for reconstructing the western side of the Ballcourt complex. Maudsley recognized that the rattlesnake rattles found in the rubble in the playing alley belonged on top of the broken serpent columns. A ballcourt ring found in the playing alley below was reattached to the ballcourt wall.

The front of the lower Temple had completely fallen away. This drawing show Maudslay's thoughts for rebuilding the fallen part of the arch and reconstructing the eastern wall. The dotted line in the drawing represents a damaged stairway found leading up to the upper Jaguar Temple. Also shown is the high vertical wall supporting the Jaguar Temple, with the sloped ballcourt walls below it.

This is how the reconstructed upper Temple of the Jaguars appeared when we visited it in February of 1993.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

The columns, pillars, door jambs, and walls of both the upper and lower Temple of the Jaguar are covered with carvings. The most detailed explanation of these figures, accompanied by an examination of intricate Itza history and mythology, can be found in Chapter 6 (Chich'en Itza: The Great Ballcourt) of Linda Schele and Peter Mathews' "The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven sacred Maya temples and Tombs". Linda Schele was a Mayanist, epigrapher, and art historian who was instrumental in the decipherment of the Maya script. Chapter 6 is probably the richest and most detailed guidebook to the art of the Ballcourt complex.

Schele questions the idea that the figures represented here are "Toltec" and, based on her readings of Landa [the Spanish Friar who recounts fragments of history about the long-deserted city], the Books of Chilam Balam [likewise, books of remembered history written in the 17th and 18th centuries in Yucatec Maya but in Roman script], and Classic-period inscriptions found in the old kingdoms of the south, makes the case that the Itza were Maya nobles who migrated north to avoid the wars that were raging between the alliances to the south. Thus, the warriors pictured here are the Itza founders of the city.

The warriors all stand on a strange creature with human face and jaguar teeth, who wears a flowered headband. Schele associates the nectar of flowers (itz) with the word for sorcerer (itz) and thinks this iconography identifies these warriors as Itza. Schele notes that the figures on the square column all have iconic name tags floating above their heads. The column facing us has a four-part flower blossom, which may be a personal name or possibly an Itza lineage name.

Linda Schele & Peter Mathews. The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs. Simon & Schuster. New York, 1998, p. 201-202, 229-230

Curator's comments:

Many of the glass plates in this collection have been published in Maudslay's Biologia centrali-americana 1889-1902. Glass negative reference for this photograph;

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

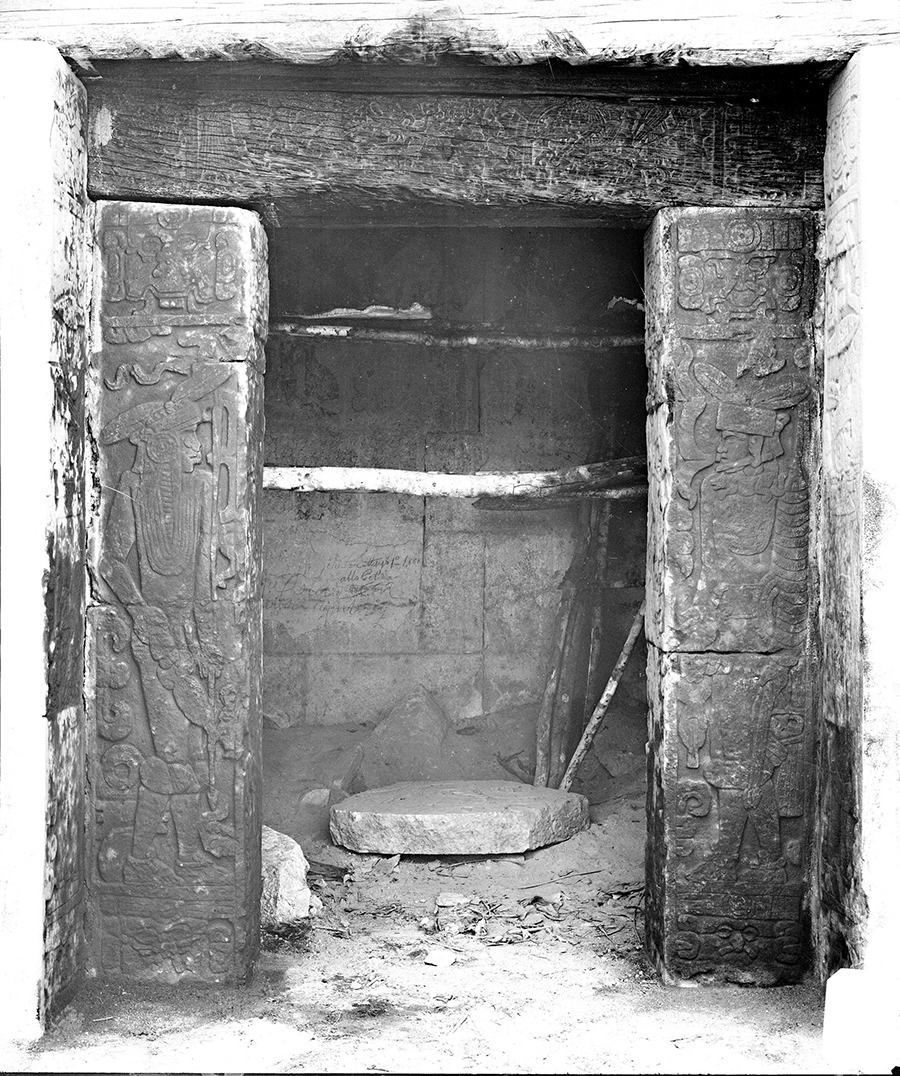

The armed warriors guarding the inner sanctum of the temple hold atlatls (spear-throwers) and have protective padding wrapped around their left arm from the shoulder down. The scroll coming from the nose and mouth of the righthand warrior is a traditional Maya indication of breath or speech scrolls. The figure on the left has a snake floating above his head as a name tag and wears a bib collar of jade beads. The figure on the right has a jaguar pectoral hanging from his collar.Schele believes these Itza warriors carved in the doorjambs are making blood sacrifices to sanctify the temple.

Note the unfortunate graffiti on the back wall. Maudslay's photos have documented many examples of this, left by early Spanish explores or by later archaeologists or passers-by who should have known better.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

The warrior on the left shows a name tag of flint-flower above his head, while the warrior on the right has a crocodile name tag. Again, they stand on traditional Maya earth monsters and wear flowered headbands, which Schele thinks identifies them as Itza. The scrolls in front of their mouths show that they are either singing or speaking.

Schele notes that individuals with a given name tag sometimes reappear in the carvings in the Lower Jaguar Temple, indicating either that the same individuals appeared in both scenes or that individuals from the same lineage appear in both scenes.

Linda Schele & Peter Mathews. The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs. Simon & Schuster. New York, 1998, p. 229-230

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Throughout the May region, carved wooden beams of sapodilla wood, which has excellent rot and insect resistance, are used as lintels over doorways. During the last century, archaeologists found many of them intact, and because of their artistic merit, were often dislodged and carted off to museums across the world. Fortunately, Maudslay made plaster casts of these lintels, leaving the originals in place.

An ancestral figure can be seen in the left half of the lintel, looking toward the left. Above him to the left is a serpent with open mouth and forked tongue. Quetzal feathers decorate the center of the lintel.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

This photo shows the back of the upper Jaguar Temple (Temple A) and the lower Sculptured Chamber (Temple E). The whole front façade and half of the supporting interior arch of the Sculpture Chamber had collapsed and lay in piles of rubble around it.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Because of the collapsed front arch and wall, Maudslay had a cut-away view of the interior of the Lower Jaguar Temple, also known as the Sculptured Panels Chamber.

Linda Schele believes that the two square columns represent the activities of two old gods who brought about the Fourth Creation (ours). "These columns depict the midwife and her husband as they enable the rebirth of their son the Maize god, so that he can initiate the Fourth creation. Between the columns sits a jaguar throne, the first stone of the Cosmic Hearth that the gods set up...By putting this jaguar throne between the midwife of Creation and her helper, the Itza declared Chich'en Itza to be the location of the first stone of Creation and Itza power to have come into being at the beginning of Creation. No wonder the Lower Temple of the Jaguar opens out onto the largest public space in the city."

Linda Schele and Peter Mathews. The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs. Simon & Schuster. New York, 1998, p. 215, 217-218

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

This pillar is to the left of the jaguar statue. A tiny part of the jaguar's back foot can be seen in the lower right of the photo.

Schele writes:"Because of missing pieces, archaeologists could not restore these columns completely, but by combining all four sides, they believe they know what the Maya meant to represent. The south column depicts four Pawahtuns, the Sky Bearers, each wearing a different kind of shell or kilt." On the north side of the column shown on the right, the god wears a snail shell, part of which is indicated by the circular lines at the top left of the column. The snail shell marks him as God N, the old god."

Linda Schele and Peter Mathews. The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs. Simon & Schuster. New York, 1998, p. 215

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

In this photo, the back of the jaguar's head and front paws can be seen to the left of the carved column. The jaguar looks away from us, into the chamber, and is armed with sharp claws.

Schele guides us through the intricate mythological symbolism of the north column, which she tells us depicts the bare-breasted goddess wearing a net skirt that identifies her as Sak Ixik, the Moon Goddess and wife of the Maize God. Other faces of the column show a skull-headed goddess stands wearing a skirt marked with concentric disks and crossed bones. This is Goddess O, known a Chak-Chel, or "Great Rainbow," who was the goddess of childbirth and the midwife of Creation. The Mams or Pawahtuns on the other column represent her husband, who became the helper of the midwife in his old age.

Linda Schele and Peter Mathews. The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs. Simon & Schuster. New York, 1998, p. 215

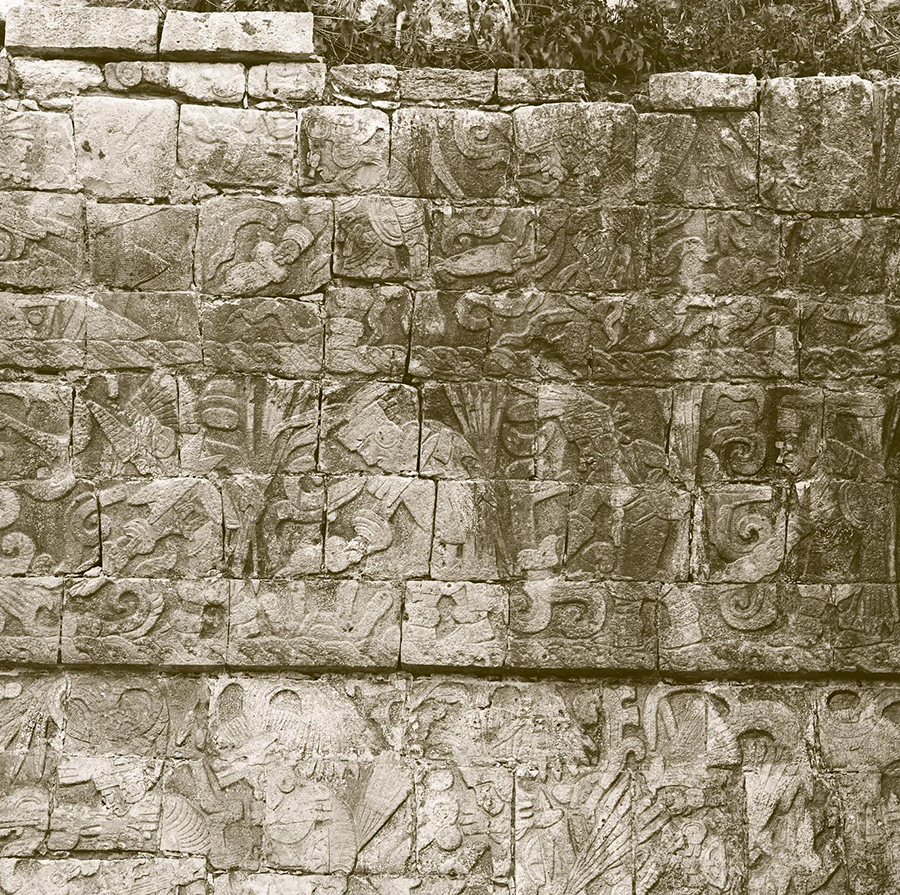

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

Only the first two or three blocks were found in place on the left wall of the chamber, so archaeologist filled in with blocks found in the rubble. Some of the repositioned blocks are more weathered than the intact blocks, and certain blocks had to be filled in with uncarved stone or concrete fill.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

The walls of the Sculptured Chamber are decorated with images of warriors which Schele believes are Itza ancestors. "They are the Ah Puh, or Toltecs —the inventors of civilized life— standing at the moment of creation in the place where the first throne stone was set up".

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

"Toltec warriors wore distinctively shaped decorative chest plates and elaborate quetzal feather headdresses into battle. They wrapped one arm from the shoulder down in padding and favored small shields which could be quickly used in close combat. For ranged combat, they had long darts which could be launched with lethal force and accuracy by their atlatls, or javelin throwers. For close combat, they had swords, maces, knives and a special curved club-like weapon inlaid with blades which could be used to batter or slash."

Christopher Minster. ThoughtCo reference site, updated May 19, 2019.

Turquoise was a significant part of Toltec culture, and Turquoise chest plates and headdresses were associated with Toltec warrior battle dress.

British Museum Curator's Comments: "One of a number of Maudslay casts from the Sculptured Chamber E, Lower Temple of the Jaguars. The cast was painted in bright colours in the second half of the 20th century, approximating the original colours in antiquity, but not as a faithful reproduction."

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

The Lower Temple of the Jaguar (Temple E with its reconstructed front wall) faces away from the ballcourt, while above it the Upper Temple of the Jaguars faces into the playing area. The small stairway seen on the left leads up to the Upper Temple.

The sculptured jaguar is can be seen between the reconstructed pillars.