The second construction phase at Chichén occurred between 900 to 1000 A.D. and included not only the Temple of Kukulkan but also the Venus Platform, the Jaguar & Eagles Platform, the Tzompantli, as well as the Ballcourt and its Jaguar Temples, plus the Temple of the Warriors and the Group of a Thousand Columns.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

Kukulkan, the Feathered Serpent, was a deity closely associated with the Itzá, and was heavily influenced by the Quetzalcoatl religion of central Mexico. Kukulkan headed a pantheon of deities of mixed Maya and non-Maya provenance and was used to promote the Itzá political and commercial agenda and adopt a political system more suited to consolidating and maintaining economic and military control.

In The Ancient Maya, Robert Sherer writes: "In the northern lowlands a Putun group known as the Itza established a new capital at Chichén Itzá and parlayed great seagoing canoes into a commanding marine trading system. From this base, the Itzá replaced the old powers in Yucatan (principally Coba and the Puuc centers) and dominated most of the peninsula for several centuries."

Robert J. Sherer. The Ancient Maya: Fifth Edition. Stanford University Press. Stanford, California, 1994, p. 434

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

The Temple of Kukulcan was in poor shape when Maudslay visited in 1889. The valuted chambers at the top were partially collapsed, and much of the stone veneer cladding the pyramid base had been loosened by tree roots and displaced.

Before photographing, Maudslay had the jungle cleared so the structure of the temple could be distinguished. The chopped off trees littering the forground attest to that effort.

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Feathered serpents of massive proportions decorated the four stairways of the Temple of Kukulkan. This photo was taken at the foot of the northern stairway.

These serpent heads and their associated balustrades were positioned so that during the vernal and autumnal equinoxes, a shadow from the stepped sides of the pyramid appears to slither down the pyramid toward the Sacred Cenote, a phenomena which draws huge crowds even today.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

The temple atop the Kukulkan pyramid showing the descending feathered serpents. Unfortunately, the serpent heads holding up the coumns are missing.

Ancient Maya temples were painted in a riot of bright colors. Remnants of original paint can still be seen on some of the interior carvings.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

Both the Venus Platform and the smaller Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars are a type of radial pyramid — flat-topped platforms with four stairways aligned to the four cardinal directions. Alfred Maudslay observes: "There can be little doubt that Nos. 13 (Platform of Eagles and Jaguars) and 14 (Venus Platform) are the two small paved "theatros de Canteria" [theaters of stone] mentioned by Landa."

A.P, Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Volume V (Text), London, R.H. Porter, 1889-1902, p. 34

These platforms, then, probably served as outdoor stages for dance, ritual performance & theater. The spaces surrounding them could easily accomodate large crowds of spectators and foreign visitors.

NOTE: Maudslay's reference to the notorious Bishop Diego di Landa is significant here, because although Landa arrived in Yucatan in 1549 and Chichén Itzá had long before fallen into ruin, it remained an important center of pilgrimage and ritual for the Maya. Landa remains a major source of information on the customs and practices of the Maya at the time of the conquest.

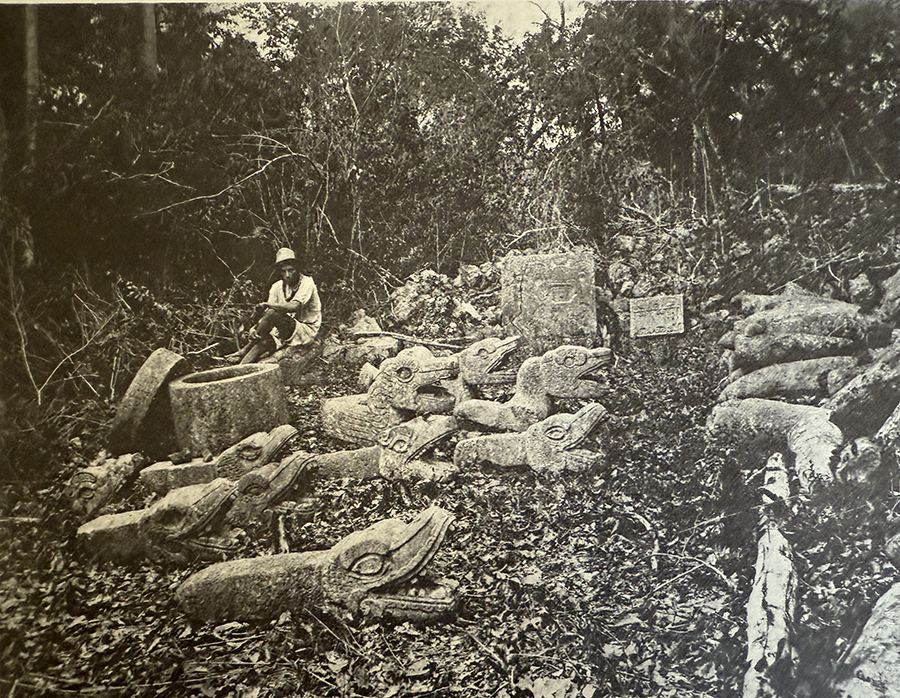

From the Maudslay Collection, British Museum. Used with permission under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 non-commercial license. ©The Trustees of the British Museum. Plate e.

Augustus Le Plongeon had arrived in Chichén Itzá in 1873, prior to Maudslay's tenure, where he discovered and named a large Chacmool statue. Ian Graham, Maudslay's biographer, describes La Plongeon as "the very archetype of the imaginative and deluded antiquary...With his bald head, penetrating gaze, long straggly beard, and confident knowledge of recondite histories, Augustus Le Plongeon must have made a deep impression in Yucatán. Some, however, were less deeply impressed, including the Mexican government, which confiscted his Chacmool, to his acute indigation."

Maudslay (who references the Venus Platform as "mound 14") writes with understandable professional exasperation: "No, 14, to the east of the last mound described, is also the scene of Dr Le Plongeon's excavations. It is much to be hoped that this mound was properly cleared, and a series of photograph taken of it before the excavation was commenced. It is very difficult now to make out its sculptural decorations, as the whole of the centre has been excavated and the stones and earth thrown over the sides, and it would have been the work of many days to have removed the large heaps of débris."

A.P, Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Volume V (Text), London, R.H. Porter, 1889-1902, p. 34

Dispite the condition of Mound 14 itself, the carving on its scattered blocks is remarkably well preserved. The image of a fish in the upper left of the photo, or the "Vision Serpent" with the human head in its jaws in the square block in the center of the photo, are remarkably clear.

Maudslay continues: "Some of the contents of this mound, dug out by Dr. Le Plongeon are figured on Plate LIII in the position in which he left them. They consist of a large number of sugar-loaf-shaped stones...and a considerable number of plumed serpents' heads. How these sculptured stones came to be buried the the mound is a mystery; the serpents have clearly at one time formed the external decoration of some building, as the end of almost every one of the stones is provided with a tenon to fix it into masonry.

He then adds "There can be little doubt that Nos. 13 (Platform of Eagles and Jaguars) and 14 (Venus Platform) are the two small paved "theatros de Canteria" [stone theaters] mentioned by Landa."

A.P, Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Volume V (Text), London, R.H. Porter, 1889-1902, p. 34

However, it appears that despite Maudslay's fears, the Venus Platform was able to be convincingly reconstructed, and presents a handsome appearance to visitors today.

It is interesting that the central panel of the platform, which Maudslay describes as "a full-faced view of a plumed dragon with a human head issuing from its open jaw" is easier to make out in the 1889 photo than in this modern photo. This is a common Maya theme, and can be seen in many Puuc sites, e.g., at Uxmal in the temple atop the Grand Pyramid.

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

Magnificent pairs of serpent heads adorn each of the stairways of this Platform.

Tzompantlis or skull racks were introduced to the Maya by the Toltecs with the appearances of the tzompantli in the Chichén Itzá ball courts. Six ball court reliefs at Chichén Itzá depict the decapitation of a ball player; it seems that the losers would be beheaded and would have their skulls placed on the tzompantli.

The travel writer Joyce Kelly notes that one of the most interesting exhibits in the Chichén Itzá Museum is a ballcourt ring, carved with a feathered serpent, that was discovered inside the Tzompantli when it was excavated.

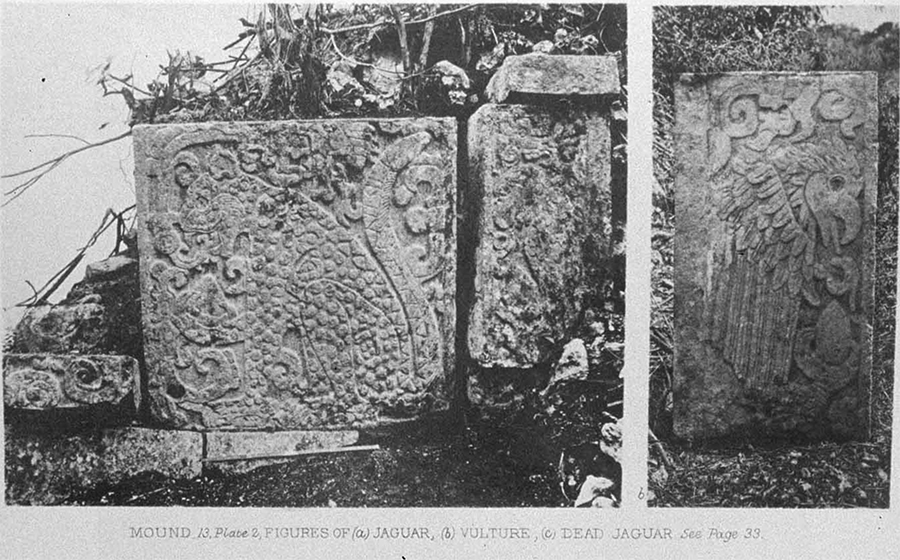

The Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars is a smaller but similar version of the Venus Platform and is placed near the Tzompantli. It is decorated with images of jaguars (central square panel) and eagles (rectangular panel to the right of the jaguar).

The "Order of the Eagles" and the "Order of the Jaguars" were the two primary military orders at Chichén Itzá, who, it is said, were responsible for obtaining victims for sacrifice. The Eagles were elite archers who attacked before the Jaguars entered fighting hand-to-hand with clubs tipped with obsidian knives. The top rectangualar panels represent prostrate human figures.

Alfred Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Vol III & IV: Plates. London, 1889–1902, Mound 13 Plate 2.

The jaguar and eagle on these panels appear to be eating human hearts, which are held up respectively by paw and claw.

Maudslay, continuing to express his frustration with the work habits of the eccentric Dr. Le Plongeon, writes: "Close to this terrace is the small mound No. 13, which is now about 12 feet high, and is approached on all sides by stairways with serpent-head balustrades. The sides of the mound were perpendicular, and were decorated with figures of jaguars, vultures, &c. Near by is lying a figure which appears to represent a dead jaguar. It is not possible to give an accurate description of this mound, as it had been the site of one of Dr. Le Plongeon's excavations, and I had not time to remove the mass of stones and earth which had been dug out from the centre and lay heaped up against the sides. But it was, I believe, in this mound that Dr. Le Plongeon found the stone figure which he names Chac-Mol, which is now in the Museum at Mexico."

Alfred Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology, Vol V: Text. London, 1889–1902, p. 33

The name "Chac-Mol" caught on, although it was never the Maya name for these figures. Such figures, in addition to the one dug up at the Platform of Eagles and Jaguars, were also found in front of the serpent columns of the Temple of the Warriors and the Temple of the Carved Columns, as well as one lying a short distance from the Tzompantli. These figures, holding offering plates over their stomachs, were probably use to hold the hearts of sacrificial victims.

A final glance backward at the iconic El Castillo from the south east

During the spring and fall equinoxes, the shadow cast by the angle of the sun hitting the edges of the platforms of the Pyramid of Kukulkan combined with the northern stairway and the stone serpent head carvings to create the illusion of a massive serpent descending the pyramid.