Geometrical alignment of temples

Knowledge of the movement of stars and of the calendar represented power to the elite class of the Maya because it related to essential food production. Knowledge and control of the manipulation of space likely was understood by every farmer who used it to lay out his milpa. At the elite level, it was used for the veneration of ancestors expressed by city planning.

Peter Harrison, The Lords of Tikal, p. 187-191.

home : : : map : : : inner-map

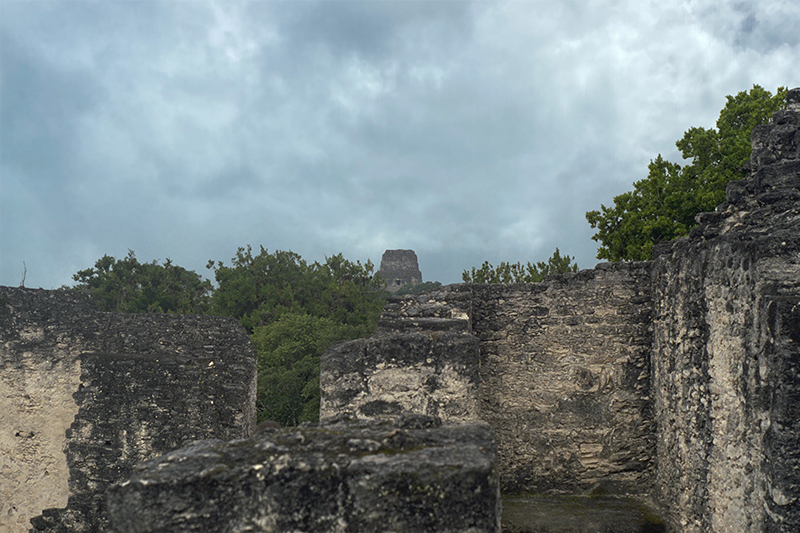

Str. 22 aligned with Temple V

Peter Harrison makes a fascinating argument about the importance of city planning to the ancient Maya. He maintains that, in determining the placement for new buildings:

(1) Each building has a single critical point in its plan that determines the location for the new building. This point is the junction of the two lines that will be formed by the front wall of the building and the central axis through the central doorway. These lines intersect at right-angles. Their point of intersection is the location point of the building.

(2) Alignment of location points was apparently important to the Maya of TIkal, so that placement of a third building in alignment with the placement points of two earlier buildings demonstrated respect or honor of these earlier buildings.

(3) The placement of the location point is established by reference to the location points of two earlier buildings which have importance to the new building. The most common reason for importance is ancestry, that is, structures raised by ancestors who will be honored by this new building. The three points, two pre-existing and one new, are connected in an integral right triangle.

In light of these observations, the layout of the city of Tikal is a massive expression of ancestral veneration over more than one-and-a-half millennia.

Peter Harrison, The Lords of Tikal, p. 187-191.

Grouping buildings by threes is a very old idea, originating back in the Maya Late PreClassic with the development of Triadic Pyramid. This style of building started around 350 BC in the Mirador Basin, spread rapidly, and because a foundational principle for later architects.

home : : : map : : : inner-map

Temple I and the Central Acropolis

The view from the North Acropolis, with Temple I on the left and the Central Acropolis in the background

home : : : map : : : inner-map

Looking toward Central Acropolis

The Central Acropolis viewed from the North Acropolis. Temple I staircase appears to the left, while Temple V appears through the mist in the far distance on the right.

home : : : map : : : inner-map

View of Central Acropolis

The North Acropolis at Tikal provides a striking view of the Great Plaza and Central Acropolis. Temple V is seen in the distance, the second tallest pyramid towering 188 feet above ground level.

The lofty roof combs at Tikal are the most massive of those in the Maya area. The exterior of the roof-comb is a solid mass, but the interior has a partly hollow core that is vaulted and sealed to lessen the weight of the comb on the temple walls.

home : : : map : : : inner-map

The Great Plaza from North Acropolis

"Nowadays we see the Great Plaza as a well manicured, grassy area. But originally it was plastered. Four different plaster floors were found a little below the present surface, dating from 150 BC to 700 AD."

Joyce Kelly, An Archaeological Guide to Northern Central America: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, 1996

home : : : map : : : inner-map

Reclining among the ancient stones

home : : : map : : : inner-map

The temples of the North Acropolis

home : : : map : : : inner-map

Temple II on rainy morning in January