Great Jaguar Claw's Palace

Chak Tok Ich'aak I (Great Jaguar Paw) accession in 7 August 360 AD and died 15 January 378

At the eastern end of the Central Acropolis there is a very special structure that had an extraordinary history. This building is now known as 5D-46, but when it was built around AD 350, or earlier, it was the clan house of the Jaguar Claw family whose name identified a bloodline and dynasty lasting through to the very demise of Tikal. Built by the king known as Jaguar Claw 1 (Great Jaguar Claw), this building is one of a very few that has been positively identified as a family residence within the Central Acropolis.

Further, it is the only Early Classic residence that was not partially demolished and covered by a later structure in central Tikal. This evident reverence for the building extended not only to the dynastic residents of the city, but to its enemies as well, during times of defeat and domination. This building was considered so sacred and so important to the identity of the city that no one dared touch it, other than to make additions and embellishments over time, and certainly, such additions were made."

Peter Harrison, The Lords of Tikal, p. 76-77

home : : : map : : : acropolis

Dedication Cache found at Palace

The stairways on both the east and west sides contained caches placed when the first building and subsequent renovations were dedicated. Each of the three caches on the east included burials, with the earliest of these probably placed by Toh-Chak-Ich'ak [Jaguar Claw] himself.

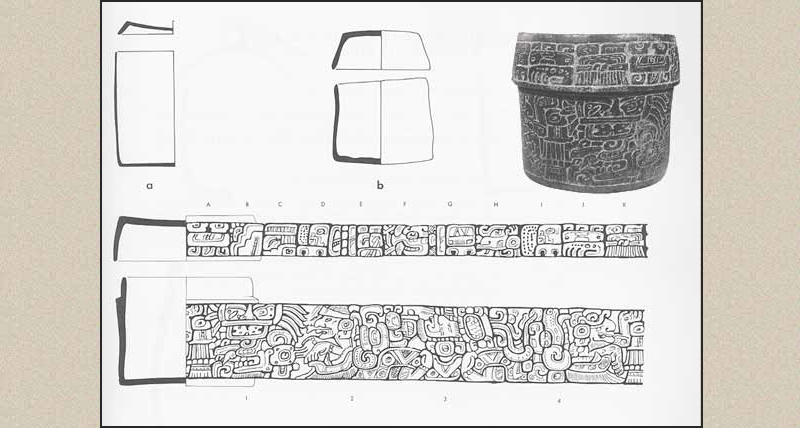

The dedicatory cache under the west stairs [shown in photo] contained the most important offering, making possible the identification of the core building as the Toh-Chak-Ich'ak's Palace. The offering included flint blades and shells arranged next to a beautifully carved cache vessel that contained a figurine, jade medallions, shell, pyrite, and obsidian mosaics...

Linda Schele & Peter Mathews, The Code of Kings, p. 77-8

West Stair Dedicatory Cache

Tikal Report 25, Part A: The Ceramics of Tikal. The Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum, 1993. Fig.108

In The Code of Kings, Schele and Matthews describe this casche in detail:

The text on this pot reads ali t'ab yotot k'ul nal, bolon tz'akabil ahaw Ch'akte-Xok, Wak Kan Ak K'ul Na, Toh-Chak-Ich'ak, Mutul Ahaw, "They say he ascended to his house, the Holy Place, the ninth successor lord of Ch'akte-Xok, Six-Sky-Turtle Holy Building, True-Great-Jaguar-Claw, Mutul Lord." This dedication text identifies the owner of the building as Toh-Chak-Ich'ak. He was the ninth king of Mutul [Tikal] and the man who led Mutul to victory over Waxaktun [Uaxactun], although he died on the day of final victory. His descendants and his vassals greatly honored him by recalling the victory in several texts, by naming at least two later kings after him, and most of all by preserving his palace as the most important lineage shrine in the city."

Linda Schele & Peter Mathews, The Code of Kings, p. 77-8

Despite this, very strange circumstances surround the death of Great Jaguar Claw and there are contradictory accounts. He died on the same day that a lord called Sihyaj K'ahk' (Fire Born) arrived in Tikal from Teotihuacan. Simon Artin & Nilolai Grube describe this entrada of AD 378 as follows:

While the term 'arrival' might seem to have a reassuring neutrality, in this case it constitutes some kind of political takeover, even military conquest. For the Maya, like other Mesoamerican cultures, 'arrival' was used in both a literal and metaphorical sense to describe the establishment of new dynasties, and this was certainly its consequence here. In what would appear to be an instance of direct cause and effect, Chak tok Ich'aak met his death — expressed as 'entering the water' — on the very same day. His demise was also that of his entire lineage, to be replaced by a completely new male line which seems to have been drawn from the ruling house of Teotihiuacan itself.

home : : : map : : : acropolis

Court for dancing & celebration

Court 4, Building 53 & 54

Across the court from the west facade [of Great Jaguar Claw's Palace], the accumulated renovations from several kings resulted in an unusual stepped configuration with the roof of one building providing a wide patio for the level above.

These patios were used for dancing in the celebrations honoring Toh-Chak-Ich'ak and his lineage. Feasting and other celebratory rituals could well have occurred throughout the spaces of Court 6."

Linda Schele & Peter Mathews, The Code of Kings, p.80

home : : : map : : : acropolis

Tikal Dancer Plates

Drawings from Tikal Report 25, Part A: The Ceramics of Tikal, Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum, 1993

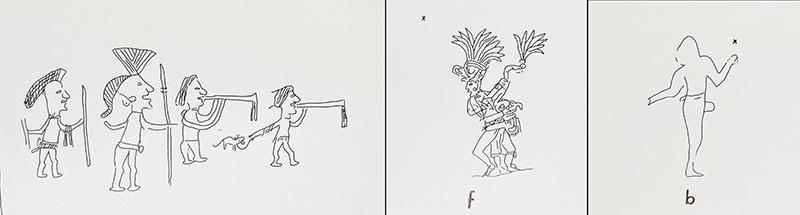

Dancers and dances were portrayed on pottery found at Tikal. Shele and Mathews write:

The ancient Maya used dance as a major part of their rituals throughout their history. Kings, lords, and commoners danced, dressed in masked costumes that represented the gods, spirits, and ancestors into whom they transformed as they performed. Painters and sculptors depicted dances like these on pots, stelae, lintels, and many other media.

Schele & Mathews, The Code of Kings, p. 82

Note: These dance portraits come from pottery found in royal tombs at Tikal.

home : : : map : : : acropolis

Mlti-level performaance stages

Buildings 53 & 54 provided multi-level stages for performance and ceremony:

The Maya left images that help us imagine the splendor and pagentry of their ancestral rituals. These drawings cannot be seen today, but they once decorated the walls of Toh-Chak-Ich'ak's throne room. One depicted a procession of befeathered lords in a ritual taking place on a series of wide terraces. In this image, some lords carry or wear branches of a plant, while others, including a couple of women, stand among huge banners."

Schele & Mathews, The Code of Kings, p. 81

Graffiti depicts ritual performance

Graffiti from Tikal Str. 5D depicts ritual performance on terraces

Helen Trik & Michael Kampen. Drawing from Tikal Report 31: The Graffiti of Tikal. The Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum, 1983, Figures p. 48

Musicians, dancers and singers

Helen Trik & Michael Kampen. Drawing from Tikal Report 31: The Graffiti of Tikal. The Univ. of Pennsylvania Museum, 1983, Figures p. 58, 67

home : : : map : : : acropolis

Court 4, Buildings 53 & 54