From a conceptual drawing of the center of El Mirador between 300 BC and 150 AD. Illustration by T.W. Rutledge ©National Geographic

Dec 2025: El Mirador, The First Megalopolis (part 1 of 3)

No road connects El Mirador to the outside world. Visitors arrive by helicopter or a three-day mule trek through the dense Guatemalan jungle. Even today, much of El Mirador's monumental architecture remains hidden under jungle flora and the debris of millennia as archaeologists painstakingly work to uncover and explore its major structures.

LiDAR technology, however, has recently transformed our understanding, revealing vast urban landscapes and far-flung networks of raised causeways interconnecting the ancient megacities of the Mirador Basin, enabling commerce, exchange of ideas, and regional political consolidation. LiDAR also uncovered evidence of ancient technologies such as water-management systems, raised field agriculture, canals, and animal corrals that enabled such a civilization to thrive in a seemingly inhospital tropical swamp. Archaeologists such as Richard Hansen, head of the Mirador Basin Project, are rewriting much of what we know and pushing the timeline for the development of Maya high culture far back into its Pre-Classic past.

In its heyday (400 BC to 150 AD), El Mirador supported a population of up to 200,000 people, developed monumental architecture which dwarfs almost anything created anywhere in the ancient world, and served as the true cradle of Maya civilization. The influence of its foundational ideas, culture, and technologies survived until the end of Maya civilization, and its myths, rituals and stories are still reenacted by indigenous Maya today. It was here that ideas of kingship, social organization, architecture, and governance, as well as writing, mathematics, astronomy, and calendrics were developed, and the arts, whose sophistication and beauty equaled anything that came later, were practiced.

First time visitor? Subscribe so you don't miss an issue!

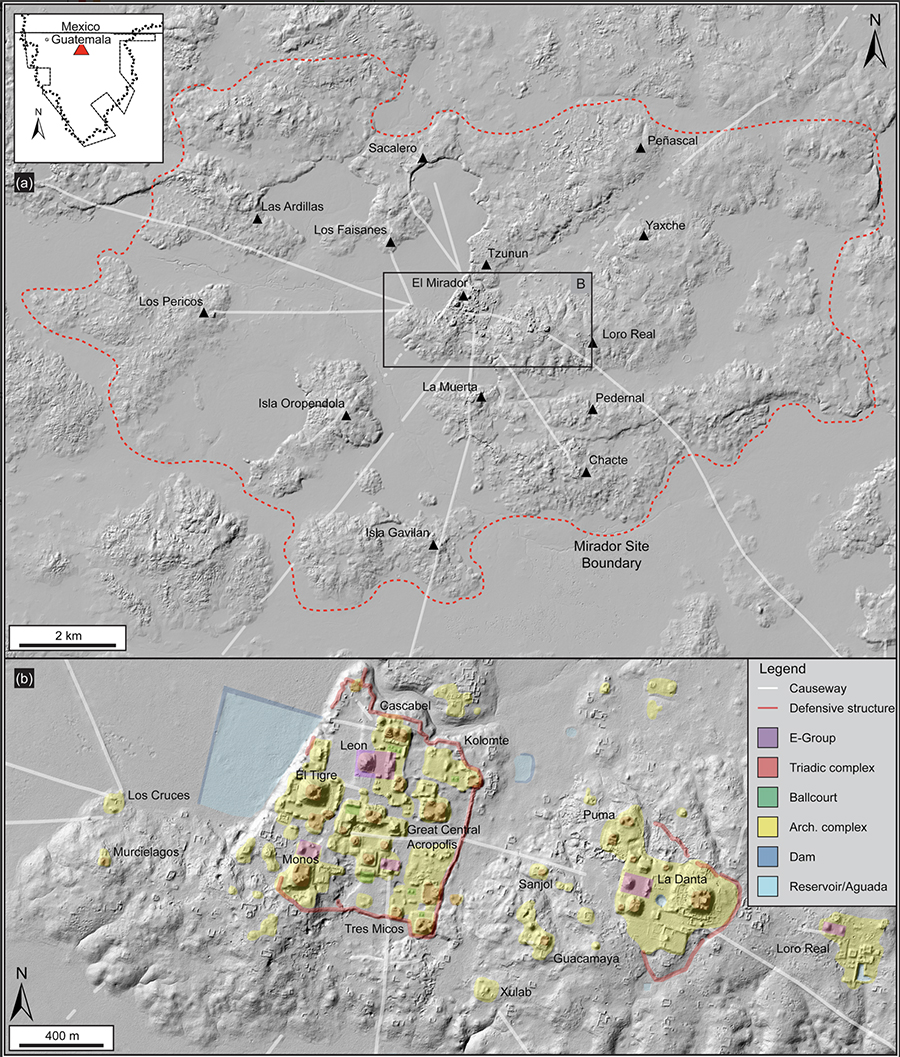

LiDAR Map of the Ancient Megacity and Regional Powerhouse that was El Mirador

From "LiDAR analyses in the contiguous Mirador-Calakmul Karst Basin, Guatemala", Hansen et.al, Cambridge University, Dec 5, 2022. Fig 16. Used under Creative Commons CC BY license

We see from LiDAR that El Mirador is located in the middle of a tropical seasonal swamp (flat areas on the map called bajos). In such areas, the Maya practiced raised-field farming along slow-moving rivers and in swampy areas and built their permanent buildings on raised outcroppings and higher ground. Canals were cut between fields and their bottom matter placed on the prepared fields to enrich the soil. Periodically, when the canals were dredged, the bottom detritus was again used to fertilize the fields.

In The Blood of Kings, the great Mayanist Linda Schele writes "...the attributes associated with this type of farming—the chest deep water, the water-lilies that grew in the canals, the fish that lived in them, the birds that ate both plant and fish and the caiman that ate everything—came to symbolize abundance and the bounty of the earth." In this way, the Pre-Classic Maya were able to sustain population densities unthinkable in modern times, with the rich muck of the bajos powering the agricultural miracle of the Pre-Classic Mirador Basin.

LiDAR also revealed an extensive and far-flung network of raised causeways called sacbey, a transportation and communication system which linked metropolitan El Mirador internally and provided long distance highways to other city-states in the Mirador Basin.

Inside the city, LiDAR identified pyramids, temples, dams, reservoirs, canals, terraces, palaces, elevated causeways, animal corrals, and other remnants of a highly evolved and complex society. We see architectural elements that were to characterize Maya cities for the next thousand years: seven ballcourts, all aligned along the traditional north-south axis, have been identified, as well as forty-two astronomical E-Groups, not to mention the monumentally striking Triadic Complexes which are seen repeatedly over the entire Basin.

Two massive Triadic Complexes dominate the skyline of El Mirador and sit facing each other at opposite ends of the city: La Danta (the Tapir) on the east and El Tigre (the Tiger) on the west. In this newsletter (Part 1 of 3), we examine the unimaginably massive La Danta pyramid and the labor and complex social organization which construction on such a scale required. Miraculously, all of this construction was done without metal tools, the wheel, or beasts of burden.

La Danta is among the largest ancient pyramids in the world in terms of mass and height

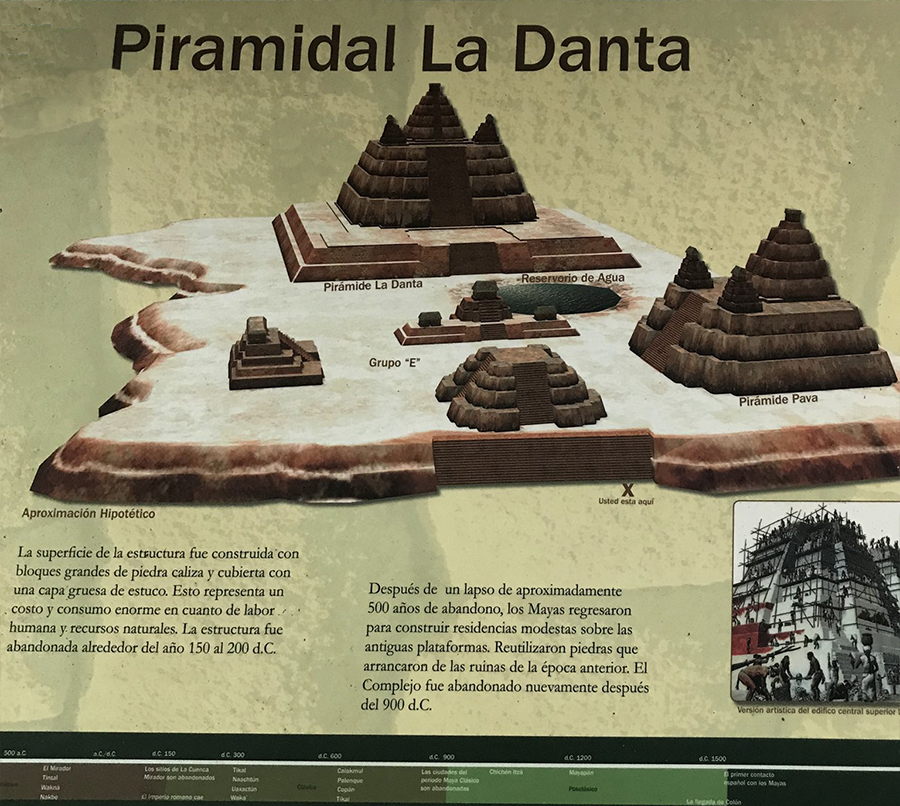

Sign at La Danta, photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

La Danta sits on a series of three plazas, each plastered over in waterproof stucco, each designed to flood during the rainy season, and each designed to channel water into storage reservoirs. In the Maya vision of the cosmos, plazas were viewed as the Primordial Sea from which the Mountain of Creation emerged, so these plazas and pyramids symbolically recreated the cosmic center of creation and the birth place of the Maize God.

Ramón Carrasco V., The Metropolis of Calakmul, in Maya. Rizzoli: NY 1998.

La Danta's plazas are immense: the lowest platform is 33 feet high, 980 feet wide and 2,000 feet deep, covering nearly 45 acres and sharing its space with other structures. The second platform rises another thirty-three feet and covers four acres. The third plaza is an 86-foot-high-platform that serves as the base for a triad of pyramids rising to the summit of La Danta (Brown, Chip. Lost City of the Maya, Smithsonian magazine, May 2011).

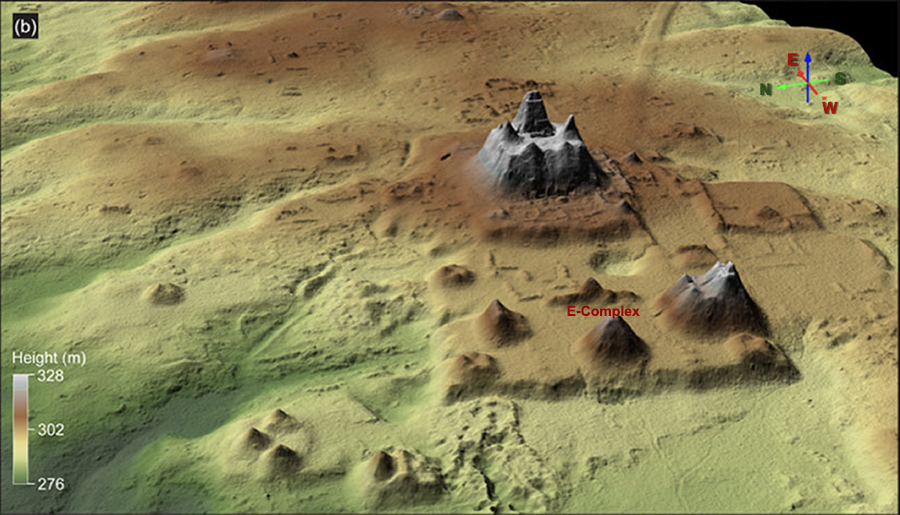

The LiDAR image from which the reconstructive drawing of La Danta was partially derived

From "LiDAR analyses in the contiguous Mirador-Calakmul Karst Basin, Guatemala", Hansen et.al, Cambridge University, Dec 5, 2022, Fig 16. Used under Creative Commons CC BY license

The Structures of La Danta were stages for ritual performance & the projection of power

A. "Horizon Astronomy" and the E-Complex

The two central structures on the lowest platform of the Danta group consist of a flat-topped viewing pyramid on the west and a smaller central building on a long eastern platform. This configuration is called an "E-Complex" and is the earliest form of Maya monumental architecture.

These complexes are an example of "horizon astronomy," the central mound on the east platform marking the exact position on the horizon where the sun, viewed from the western pyramid, rises during the summer solstice. The side mounds on the northern and southern ends of the platform marked winter and summer sunrise equinoxes, or could be placed at different locations to mark other pairs of calendrical events significant to an agrarian economy. These complexes first appear in the middle Pre-classic, as early as 1000 B.C., and were ubiquitous throughout the Mirador Basin. They demonstrate how the Maya incorporated solar and other astrological phenomena into their architecture and city planning from an early date, thereby dramatizing and ritualizing events of the agricultural calendar. At least eight E-Groups have been found at El Mirador.

B. The Triadic Form

The Danta pyramid is an example of the Triadic Architectural Form, the most massive architectural style to originate in the Mirador Basin. It consists of a major structure facing a central stairway, with smaller structures on each side facing each other and at right angles to the central structure. This feature appeared suddenly and ubiquitously throughout the Mirador Basin by the early Late Pre-classic period (350 to 300 B.C.) and possibly evolved from the eastern platform of the E-Complex, although later triadic groups do not always preserve their eastern orientation.

Recently, however, scholars have begun to associate the triadic symbolism of these buildings with the Maya three hearth-stones of creation, believed to be the three stars in Orion's belt plus the cloudy area they enclose (the Great Nebula M42) which represents the smoke from the fire of creation. There also, the Maize God was born from a crack in the carapace of the Cosmic Turtle (also identified with the constellation of Orion), his birth assisted by his sons Hunahpu and Xbalanque, the Hero Twins.

The birth of maize god from the cosmic turtle in Orion, assisted by his sons, the Hero Twins

Codex-style plate, MFABoston, Mirador Basis, AD 680-740

In any case, a new worldview is implied by the development of the triadic architectural form, for the ritual platform where celebrations occurred is now raised massively above the two lower planforms, creating a restricted sacred precinct accessible only to high kings and high priests. Imagine the spectacle of a summer solstice celebration, when the high king, at the moment of dawn and surrounded by chanting and the playing of drums and turtle carapaces, emerges from the central doorway of the highest temple at the exact moment of sunrise directly behind the temple.

The unimaginably massive La Danta, its LiDAR-visible side temples still obscured by jungle

Drone view of the La Danta Pyramid complex, El Mirador. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

License: Public Domain (CC0). View extra-large 3468x2874px source photo

La Danta is 75 meters high, the equivalent of a 26 story modern office building. It is the greatest example of the mass mobilization of labor overseen by the Late Pre-classic kings of El Mirador. The construction and maintenance of gargantuan public works were designed to serve both practical and esoteric needs of the inhabitants of ancient El Mirador. The sheer volume of construction material, the millions of man-days required for construction, and the complexity of the political and economic systems required to support and organize such an effort is staggering.

Hansen, Richard D. Cultural and Environmental Components of the First Maya States: a Perspective from the Central and Southern Maya Lowlands, p. 13

Richard Hansen leads the Mirador Basin Project in Guatemala. He was instrumental in the LiDAR mapping of the Mirador Basin, publishes scholarly works in both English and Spanish on Maya archaeology and anthropology, and shares his discoveries and lectures freely on the Internet and in social media. He works tirelessly to preserve the tropical jungle of the Mirador Basin, and to insure that the Maya of the region benefit economically from their ancient culture and the potential tourist dollars it can bring.

Who better, then, to explain his research on how these ancient structures were constructed and how he estimated the amount of labor involved in their construction?

The stonework of La Danta demanded quarry and stonemason specialists of a high order

Photo courtesy of Jeff Percell

The construction of La Danta was made possible by the unprecedented level of social organization and architectural specialization during the Pre-Classic period (c. 1000 BC—AD 150) and the rise of construction specialists.

During the late Middle Pre-Classic period, the size and form of quarried stone changed dramatically. Builders moved away from rough, simple stones toward much larger blocks of consistent size and form — often measuring up to a meter long and half a meter wide.

This standardization and the technical expertise required to consistently produce such stone blocks points directly to the existence of dedicated quarry and construction specialists and the employment of full-time masons. This specialist production system for stone extraction was a foundational development that survived for the remainder of Maya prehistory.

A common and significant feature was the use of beveled tenon blocks. These were impressively large stones placed on the façade and flanks of structures, with their long axes deeply embedded into the building's core. The exposed area of the block was then sloped. The use of these large, custom-cut blocks represented a maximum investment of labor per stone — a defining trait of the Mirador Basin structures.

In contrast to the later Classic period, the Pre-Classic masons of La Danta deliberately chose to maximize the labor per stone to create deep, robust, and monumental façades. This choice reflects the power, centralization, and mobilization capabilities of El Mirador as the first true state-level society in the Western Hemisphere.

Hansen, Richard D. Continuity and Disjunction: The Pre-Classic Antecedents of Classic Maya Architecture. In Houston, Stephen (editor), Function and Meaning in Classic Maya Architecture. (Dunbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington D.C., January 1998, p. 71, 102, 103, 105, 150)

By these stairs one reaches the upper plaza, from which the triad of crowning pyramids emerge

Photo courtesy of Jeff Purcell

The lofty third plaza of the Danta Group is a restricted sacred space far above the lower plazas. The plastic overhead covering and the brown tarp were put in place by Hansen's team to protect from jungle torrents and the effects of the tropical sun.

From the third plaza, the now bifurcated stairway circles toward the dominant pyramid's top

Photo courtesy of Jeff Percell

This stone stairway, part of the ancient construction, shows the Pre-Classic blocks that formed the step armatures of the stairways. Although not all Pre-Classic buildings had these stones, they are rectangular, finely cut, long stones measuring up to a meter long and half a meter thick and are found at Pre-Classic construction at Tikal, Uaxactun, Nakbe, Tintal, and El Mirador. They are similar to wall blocks that formed the terraced walls of Middle and Late Pre-Classic structures, except that a long side of the stone is beveled to form the exposed riser. (Hansen, Continuity and Disjunction, p. 100)

Early pilots flying over the Mirador Basin in the 1930s thought these pyramids were volcanos

Photo from Google Maps

In "El Mirador, the Lost City of the Maya," Chip Brown recalls flying over the jungle of northern Guatemala with Richard Hansen, the director of the Mirador Basin Project. As they circle the massive structures hidden beneath the dense forest canopy, Brown notes that "the pilots who first flew over the Mirador basin in the 1930s, among them Charles Lindbergh, were startled to see what they thought were volcanoes rising out of the limestone lowlands. In fact, they were pyramids built more than two millennia ago, and what we were circling was the largest of them all, the crown of the La Danta complex."

Brown, Chip, Photos by Christian Ziegler. Lost City of the Maya. Online PDF: Smithsonian Magazine, Vol 42 No 2, May 2011.

The final climb to the pinnacle is via a rickety wooden stair improvised by the archaeologists

Photo courtesy of Jeff Percell

The trees in this photo are growing out of the sides of the pyramid, the actual jungle canopy lying far below. Only the front and top of the pyramid has been cleared, while the other faces are left uncleared for several reasons, among them to shade and protect the pyramid from ultraviolet light, to preserve the natural jungle habitat and its creatures, and to leave untouched areas for future archaeological study.

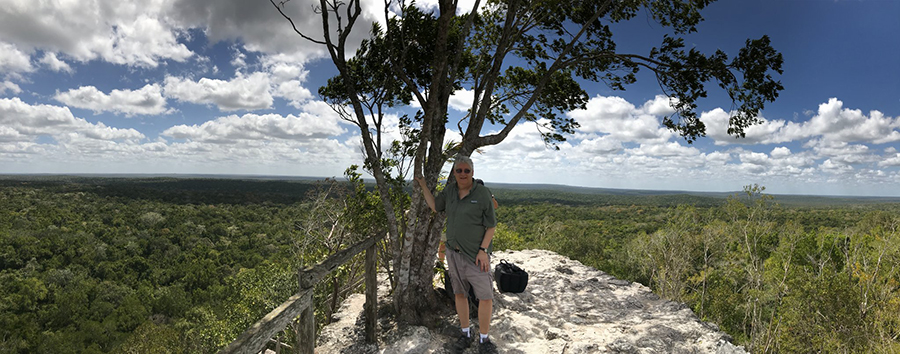

La Danta rises high above the jungle canopy and delimits the eastern precinct of the city

This is Jeff Percell, our friend and intrepid climber who donated all the photos featured in this newsletter. Thanks, Jeff!

La Danta pyramid has been compared to an "artificial mountain." It soars above the highest jungle canopy, as well as above the secondary jungle growning out of the raised plaza from where the triadic pyramids emerge. Its height is estimated to be equivalent to a 26-story modern building.

Our friend and adventurer, Tom Schuler, who originally initiated the idea of going to El Mirador

Photo courtesy of Jeff Percell.

If you look very carefully at the jungle in the background, you might be able to see slightly raised lines of trees running diagonally on the right side of the photo. These are raised mounds which still mark ancient sacbey (highways) which connected El Mirador to distant cities in the Mirador Basin.

It is hard to imagine that this isolated and virtually uninhabited area of swampy tropical jungle once supported a population of up to 200,000, or that the whole Mirador Basin was once a network of unimaginably large, highly developed, and interconnected cities and settlements supporting a population approaching one million people.

Hansen believes that the Pre-Classic Maya were part of what he defines as the five original "foundational civilizations" in world history. He sees these cultures as "foundational" because they developed the earliest complex social organizations and technologies including writing and mathematics. It is interesting that all the other seed civilizations developed along rivers -- the Nile, the Tigrus/Euphrates, the Yankzee, and the Indus Valley civilizations, so the Maya in the Mirador Basin swamps were unique.

Our January 2026 issue, Engineering of the Swamp, will continue with an examination of the technology, infrastructure, and agricultural practices which allowed El Mirador to thrive in this seemingly inhospitable environment.

We welcome questions, comments, photos, travel stories, & other musings, and will share selected contributions in the February 2026 Newsletter.