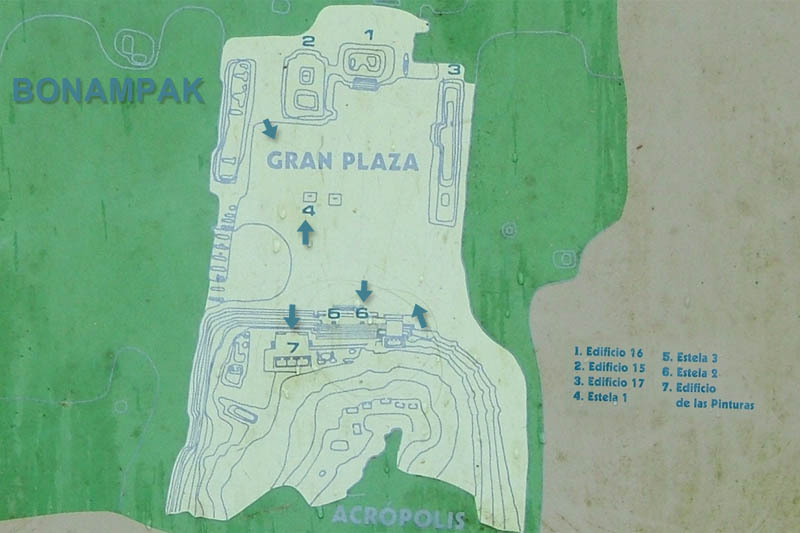

Map of the Ruins of Bonampak

Map at site adapted from Maria de la Cruz Paillés "El nuevo mapa topográfico de Bonampak." Click on ARROWS to view photos (or continue scrolling for Room 1 murals), or here for an annotated Bonampak reading list.

A Note on the Murals of Bonampak

Bonampak’s murals and stelae vividly portray royal ceremonies which took place from 790 to 792 A.D. and were overseen by its ruler Chaan Maun II to celebrate the investiture of his infant heir. Dr. Mary Miller, the art historian who documented the murals, believes the murals were never completed, and that Chan Mauin II and his family perished shortly afterwards in a bloody battle much like that depicted in Room 2.

Miller informs us that the preservation of the paintings was a fluke. Shortly after their completion in the late eighth century, water began to seep through the poorly made limestone vault, building up a protective layer of calcifications that encased the fragile stucco paint. The murals were “discovered” by an American, Giles Healy, who was sent to Chiapas by the United Fruit Company to make a nature film. In 1946, a Lancandon Maya, Chan Bor, took Healy to see this previously unknown site. The colorful story of Healy, as well as first–hand details on the restoration of the murals, are related by Miller in her fascinating Yale University lecture.

It is sobering to realize that by the time the murals were completed, Bonampak was suffering from deforestation, exhausted farmland, overpopulation, and endemic wars, yet the murals themselves are an ostentatious display of extreme wealth and opulence. By 900 A.D. Bonampak, as well as its patron state Yaxchilan, had completely collapsed and were abandoned. Elite society in the region ended and forest reclaimed the area. Later when the Spanish arrived they found the area sparsely inhabited. The Lacandon Maya in this area then fled into the deep jungle to preserve their ancient customs and to avoid contact with the invaders.

Mary Ellen Miller and Claudia Brittenham. The Spectacle of the Late Maya Court: Reflections on the Murals of Bonampak. The University of Texas Press. Austin 2013.

The Bonampak Acropolis

We visited the acropolis of Bonampak on a rainy morning in January of 2004. Structure 1, containing Bonampak’s famous murals, was under a protective awning at center right while the gigantic Stela 1, protected by a canopy, dominates the foreground of the photo.

Bonampak's ancient placename is proposed to have been Usij Witz or Vulture Hill. The hill rising in the background probably carried that placename.

David Stuart, Maya Decipherment Blog, Bonampak's Place Name, University of Texas at Austin, December 2006

The Acropolis in 1971

Photo courtesy of Paul Tanner. Thanks, Paul!

Even though Bonampak was “discovered” in 1946, the site remained inaccessible and little changed even twenty–five years later. This photo was sent to me by Paul Tanner, who gives us a rare glimpse of how the site looked in 1971 before most of the archaeological restoration took place. There is an interesting video lecture from Yale University featuring art historian Mary Miller, who talks about her work restoring the murals as well as relates interesting gossip about the eccentric early explorers, archaeologists, and art historians who worked to restore the site.

1971: Lancandon village near the ruins

Photo courtesy of Paul Tanner

During his 1971 visit, Paul Tanner stayed at a Lacandon village near the ruins. At that time, most of the Lancandon wore their traditional long tunic called Xicul and had little contact with tourists.

Room 1, Edificio de las Pinturas

Note: I used Photoshop's "Exposure/Gamma Correction" feature to darken the photos and enhance colors. The actual murals are considerably more faded.

Let us now begin our tour with the spectacular murals of Room 1 of the Edificio de las Pinturas, where vivid horn players announce a celebratory ritual taking place. Bonampak's unique importance comes from the vivid portrayal of Classic–era court life in its murals, considered to be the finest so far found in Middle America.

The orange hieroglyphic band

An orange band of hieroglyphic text divides the mural into two zones.

The upper paintings show the presentation of Chan Muan's royal heir to an assembled court of fourteen Ahaus dressed in long white mantles. According to the date in the hieroglyphic text, this event took place on December 12, 790 A.D.

The lower paintings show musicians and dancers in a celebration honoring the new heir. This occurred on longcount date 9.18.1.2.0, or November 15, A.D. 791, a day when Venus first rose as Evening Star. This date may have been chosen to assure that the young dynast would become a great warrior. A broad cross-section of the Maya hierarchy attended this celebration at court.

Schele & Miller, The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art, p. 148

The upper register

The story starts in the upper register, where the new heir is presented to assembled Ahaus on longcount 9.18.0.3.4, or December 14, A.D. 790.

From a chamber in a multi-galleried palace [off camera], King Chaan-muan, attended by his wife and some children, directs the proceedings while portly Ahaus in white robes give their sanction to the child, ensuring his status as a legitimate member of the lineage. This scene is underscored by the text and framed by the parasols that reach from the lower register.

Schele & Miller, The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art, p. 148

NOTE: The small turquoise rectangles above each of the participating dignitaries served as a name tag where titles and names were inscribed. Not all the name tags have been filled out, perhaps because of shifting political alliances or other considerations.

Status dressing

When you go to court, you wear your best stuff.

The most important lords wore blinding white capes closed at the throat with three huge red spondylus shells. This cotton garb was reserved for those privileged to serve as attendants to the king, or those who held the status of pilgrims to the royal festivals.

Schele & Freidel, A Forest of Kings, p. 278

Assemblage of Gossiping lords

The last four of the fourteen lords are painted in the triangle-shaped section of the east wall of the vault. Only two of the four are visible in the photo.

Notice the beautiful woven fabric of the kilt worn by the Ahau third from the right in the photo. Stela 2 also has exquisite representations of the beautiful woven fabrics worn at court.

The Lower register celebration

This celebration took place 336 days after the young heir was presented to the court of Ahaus shown above, on the date when Venus first appeared as the Evening Star. Because Venus was a male god of war, the dance ritual shown below might have been timed to insure that the new heir became a great warrior.

Between the trumpeters and the corner of the room, dancers wave huge crustacean claws and two individuals dressed in exotic costumes appear engaged in some ritual activity. A parade of percussionists appears in the right–hand side of the photo.

A parade of percussionists

A parade of percussionists play turtle carapaces, drums & large gourd rattles. Three turtle–carapace players on the left follow gourd players in the procession, with a drummer playing a chest–high drum between the two groups.

In this Bonampak scene, then, the “musicians” are not just playing music, they are participating in the conjuring of powerful supernaturals into the festival arena.

Freidel, Schele & Parker, Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman's Path, p. 257 & 453

Note: Ethnomusicologist John Burkhalter demonstrates how the Maya used gourd rattles for percussion during their ritual processions and what they might have sounded like in this short video from the Penn Museum. Other short videos demonstrate the Maya jaguar drum, the Maya conch shell, and discuss Maya music as imitating animal, bird, and other sounds in the natural world in relation to musical performances depicted on painted Maya pottery.

Turtle carapace players

Closeup of two turtle carapace players. The turtle carapace was an important percussion instrument in ancient Mexico and Central America. It was beaten with deer antlers, could produce multiple tones, and had a mournful, otherworldly sound perhaps associated with the primordial sea.

The virtuoso drummer

On the lowest register of Room 1, Maya musicians and regional governors flank the dancers at center. Here the Maya artist attempts to represent aspects of movement and sound otherwise unknown in Maya art.

The maraca players move as if in stop motion, their arms changing frame by frame; the drummer’s hands were painted with palms turned to the viewer, his fingers clearly in motion. The casual examination reveals only the blur. In this, the painted wall attempts to represent sound itself in the drummer’s fluttering hands.

Mary Miller, Maya Art and Architecture

NOTE: Like the infant prince on the upper register, these figures have had their eyes defaced, presumably to nullify the power of the mural.

Maraca players perform in stoptime

A column of maraca players perform in stoptime.

The first five [musicians] wear tall white headdresses and painted leather skirts and they shake large magical gourd rattles.

Mary Miller, Maya Art and Architecture

Hieroglyphic name tags

The nobles, identified by small hieroglyphic name tags, wave huge fans. The yellow “T-square” is a name tag giving the name and rank of the participant in hieroglyphic characters.

They hold huge parasols or fans which break the symmetry of the orange band separating the lower and upper registers.

Closeup of exotic headgear

This figure appears to be wearing a skull on the top of his turban. Among the Aztec, warriors could only wear a skull headdress if they had captured two prisoners. Perhaps the Maya had similar requirements.

Note the partially faded glyph between the fan handle and the skull. Could that be a comment on the ceremony? Could it have been added later? In any case, it doesn’t have the contrasting background that mark other name tags.